He was laughing so often! Researcher Krystyna Cech recalls conversations with Yongdzin Rinpoche

For more than two years, from 1982 to 1984, Krystyna Cech lived in Dolanji, the main Bönpo refugee exile settlement located in the Solan district of Himachal Pradesh in India, observing the life of the community. She based her doctoral thesis on that fieldwork. During that time, Krystyna spent many hours talking with Lopon Tenzin Namdak – as he was humbly and commonly called at that time – the lama who played a key role in securing a safe place for Tibetan refugees of the Bön religion to settle and who was to become the most revered teacher of the global Bön community. His Eminence Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche – “Lopon” – passed away on the 12th of June of 2025, after reaching one hundred years of age. This interview is dedicated to Rinpoche´s memory and is published the day after all the purification rituals were concluded at Shenten Dargye Ling, on the occasion of the Bön Losar falling on the 19th January this year.

Krystyna, what went before you started your research in Dolanji? How did you choose it?

After I finished my first degree, which was in sociology, I travelled to Asia. I spent some time in Japan and when I was slowly making my way back home to England, I stopped over in Kathmandu, where I intended to stay only briefly, but ended up staying for two years. I applied for a Royal Nepal Academy fellowship to do a project about women. I chose to do it in a village near Dhankuta in eastern Nepal among the Athpariya Rai people. The project was accepted. I lived in the village for six months observing the way of life of the villagers, especially that of the women. On one of my treks north of the village I came upon a train of yaks coming along a trade route (carrying salt, I think) through a small town from further up north. For some reason it made a huge impression on me – an intimate encounter with the people and animals from the northern area of Nepal where the culture was influenced by Tibet. After that, I wanted to find out more about Tibetan culture. When I returned to England and was planning my PhD at the University of Oxford, I decided to do it in anthropology, not in sociology, and the aim was to continue to explore the life of people rooted in Tibetan culture.

The title of your thesis is The Social and Religious Identity of the Tibetan Bonpos with Special Reference to a North-west Himalayan Settlement. Did you choose this subject right away, or did it emerge in the process?

At the time I was choosing the subject, not much had been published about Bön. When it was mentioned in the literature, it was described mainly as a kind of shamanic religion with somewhat mysterious and magical rituals. I got intrigued and wanted to know more about this “Bön religion”. But in the process, I discovered that many of the rituals attributed to Bön were also present in Buddhism; they were more a universal feature of Tibetan culture than something specific to Bön alone. As I came to understand this, the focus of my research gradually shifted and I realised that Bön could not be understood without reference to Buddhism and Buddhism could not be understood without reference to Bön. I then started looking for a place and a community with whom I could do my fieldwork.

What brought you to Dolanji? How did you find the community living there?

I went first to Ladakh. There I happened to meet Tadeusz Skorupski, a Tibetologist working with Professor David Snellgrove from the University of London. Professor Snellgrove had invited three Bönpo monks to England in the 1960s to help him with his textual research. One of those monks had been Lopon Tenzin Namdak and the other two were, soon to become, Abbot Sangye Tenzin and the now renowned scholar, Samten Karmay. Tadeusz told me about the settlement of Dolanji where Tibetan Bön refugees had gathered and built a monastery. I decided to go and have a look. When I arrived at Menri monastery, I met the abbot, 33rd Menri Trizin Lungtok Tenpai Nyima, whom I knew as Sangye Tenzin. He was very welcoming. He spoke good English after his three years in England with Professor Snellgrove. When I explained that I wanted to do research on folk religion, he laughed and said: “I don’t think you’ll find it here.” But he told me I could come and do my fieldwork. After meeting him, I met Lopon Tenzin Namdak and got his consent as well.

How old were you then?

I started my fieldwork when I was twenty-six, and this first visit was some months earlier, in 1981. On that occasion I stayed only for a couple of days, just long enough to see whether I could obtain permission to do my research there.

Why were they so quick to say yes, what do you think?

I think it was the connection with David Snellgrove, through Tadeusz Skorupski who had directed me there. Also, I believe that I was welcomed because both Lopon and the Abbot had a good impression of western-style research after living and working in an academic environment in England.

When exactly did you come, and how long did you stay?

I started my research in January 1982 and finished in May 1984.

Did you stay there the whole time?

Yes, I was there for most of the period, apart from one visit to Europe. Menri monks had been invited to perform cham, the sacred dance, on a tour that included France, Belgium and Germany, and I went along with them to help. It was very interesting for me to see how they were projecting their Bön identity. Lopon Tenzin Namdak did not go, but the abbot did and was in charge of the whole group of about twelve monks, all of them very young, in their early twenties, apart from two older monks. Before they left for the tour, there were plenty of rehearsals – they were just young things and had to be taught the precise dance steps. Then the costumes had to be made, and the Bön hats had to be made…

Where did you live in Dolanji?

There was one small guestroom at the monastery. It was basically just one room where anyone visiting would stay. There were visitors from the West already there at that time. For example, the excellent musicologist Ricardo Canzio came to record Bön ritual chanting accompanied by his wife, Priscilla, a photographer…

I stayed in that guestroom for a while, even though it was within the monastery. It was a bit unusual for a woman to be staying in the monastery, but it felt as if I had a kind of carte blanche; I was allowed to go almost anywhere. Not into the monks’ rooms, of course – that was forbidden, and understandably so. I stayed in the monastery guestroom for three months, but I wanted to be in the community, in the village part of the settlement. So, Abbot Sangye Tenzin arranged for me to stay in a house down in the village in a row of houses called Amdo Line, where people originally from Amdo had settled. I lived in one of those houses.

What were your living conditions like? For example, what kind of toilet did you have?

There was an outdoor toilet. You had to walk a little way down the slope. I shared it with the family next door, who kindly allowed me to use it.

Did you have electricity?

Yes, we had electricity.

And water? How did you get water?

There were water tanks higher up on the hill. Each family could fill their own individual tank at certain times, through a water hose.

Did you prepare your own meals?

There were three families I regularly went to for my meals, taking turns from week to week. They were all from Amdo. Abbot Sangye Tenzin was from Amdo, so he knew those people well and, in a way, could keep an eye on me.

How did you speak with them – in which language?

They didn’t speak English, but I was learning Tibetan and spoke Tibetan with them. The longer I stayed, the more fluent I became. It was full-immersion learning. One difficulty was that there were people from different areas of Tibet in the settlement, and they spoke different dialects. As I said, there was a line of houses with people from Amdo, who spoke the Amdo dialect. Then there was another section of the settlement where people came from Ü-Tsang, the central area of Tibet, another where people were from western Tibet, and another from Kham. They all knew central Tibetan, but if they wanted to say something that I shouldn’t understand, they would slip into their own dialects, and I had no idea what they were talking about. Once they spoke central Tibetan, however, I could follow.

There were only Bönpo families in the settlement, right?

Yes, they came to live there because they were Bönpo. They felt more secure there. In those days, the Bön religion was not regarded very favourably by other Tibetans. Lopon Tenzin Namdak chose the site also because it was not easy to reach. He thought their daily life and religious practices would not be interfered with so much by other Tibetans who were not Bönpo. The atmosphere at that time was somewhat fearful, the general attitude towards Bönpos was rather unfriendly.

Dolanji at that time was indeed difficult to reach. There was a bus from Solan to Kalaghat, and after that you had to walk about five kilometers to the settlement. There was no proper road. The monastery did have a battered jeep, which they used once a week to buy supplies in Solan, but the journey was quite precarious.

How did you structure your survey in the settlement?

Initially, I had a set of questions and went from house to house with them. First, I asked where people had come from, who they had come to India with, and the story of their escape from Tibet. It wasn’t that long after 1959, just a little over twenty years – so they had very vivid memories of escaping, and of the hard life they had at the beginning in India. The settlement wasn’t founded until 1967, so between 1959 and 1967 they were scattered in different places and doing very hard physical work. Many of them had helped build roads, both men and women, and it was extremely demanding physically.

What did they do to make a living by the time you were there? What was their work then?

Mainly trading, and a little agriculture, although the land there wasn’t very good for farming. In the winter season they used to buy Indian-made machine-knitted acrylic sweaters and then they went to places like Calcutta for two or three months to sell them. There was great demand for these sweaters in winter because it does get chilly in north India. Many of them earned enough money to live quietly in Dolanji for the rest of the year.

The population of the settlement went down in winter because so many people left to do this trading. They all returned for Losar in February, bringing money and new clothes for themselves and their families. I’m not sure if they still engage in this kind of trade. When I was there last year, I didn’t have enough time to find out.

What did you ask them about their religion?

I was interested in domestic rituals – in the situations when a family or household would ask monks to come and perform a ritual for them. Almost invariably, it was when someone was sick. The ritual didn’t have to be performed in the monastery; it could be held in their homes, as each house had its own household shrine. Four to six monks would come to perform a commissioned ritual. If the household was wealthy, they might commission the rituals in the monastery itself. It seemed to be the rule that the householders would always invite monks from the region of Tibet that they came from originally to perform rituals for them.

During those more than two years, you spent many hours talking with Lopon Tenzin Namdak, or Yongdzin Rinpoche, as many call him. What were the circumstances of your conversations, and what did you talk about?

He was very busy teaching the monks in the Dialectics School, but I always felt welcome. Perhaps he wanted to speak English to me. Sometimes, more rarely, he was busy and said: “Oh no, not now.” Otherwise, I was always given tea and made welcome to sit and listen.

He shared the story of his life. But it was not just about himself; he would tell you all about his village and his family. He spoke very fondly of his mother. He often mentioned, with a certain pride – if that is the right word – that she had lived to a great age. I think she reached 104. Perhaps that is where he got his longevity from.

We also did some translations together. He would read a text in Tibetan and then give a rough translation in English. I would write that down and then put it into slightly better English. The last thing we worked on was his Pilgrimage Guide to Tibet, and I am very sorry that I did not finish that translation with him. We probably got about two-thirds of the way through. For each place mentioned he could add so much more information, because he had been there. He had an extremely good memory.

Was he curious about the West and your life? Did he ask you questions, or was it more you asking and him explaining?

No, he wasn’t particularly interested in western things. He had already seen the West with his own eyes. He was not inquisitive in that way, and he was not a worldly person. He was more intent on teaching his monks and helping them become geshes. The abbot, Sangye Tenzin, by contrast, was very interested and always curious about how things were. He liked gadgets – for example, a wristwatch with many functions.

They were very different from each other. The monks used to call them the father and the mother of the monastery. Sangye Tenzin was the father, he was more strict, he was the disciplinarian. I could never imagine Lopon Tenzin Namdak disciplining anyone. He would talk to the monks, tell them they were wrong about something, but he would not discipline them as such. I never saw or heard of him doing that.

Did the two lamas have meals together?

No, they ate separately. Lopon Tenzin Namdak’s house was outside the monastery. He had his own little private life down there, teaching. He came up to the monastery for rituals and so on, but they did not eat together; they had separate establishments.

Did Youndgzin Rinpoche – Lopon Tenzin Namdak – teach in his own house?

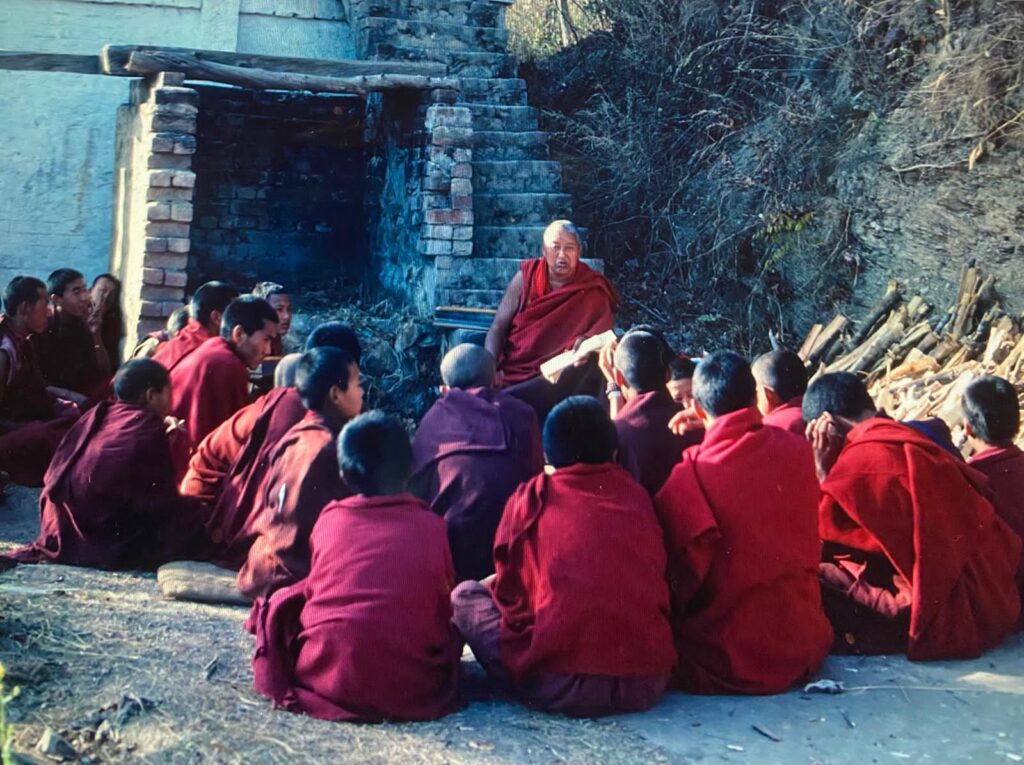

Yes, there was a teaching room there, but quite often he taught outside, in the courtyard.

Who was cooking for him?

His monks. He had a group of monks living with him, and they cooked for him. One of them was Tenzin Wangyal, who later became a renowned teacher in the West. He was a very young monk then, and extremely hardworking at his studies. He was probably the star pupil of Lopon Tenzin Namdak. He was very generous with his time to me as well. When I had questions, I often asked him, and he would ask Lopon. He was an important influence on me while I was there. When he was in London last year for several weeks, I arranged to see him and we talked about old times. I showed him all the old photographs, and we spoke about the monks from his group whom I had met in Dolanji. “He’s in Norway, this one is in Germany.” They are scattered. There is a demand for them to teach.

Did you have lunch with Lopon sometimes?

I didn’t really share meals with him. I used to have tea with him. But I did share meals with Abbot Sangye Tenzin. Quite often I would simply eat what he was eating. He liked to digress over meals. If I asked him a question, he might begin to answer and then digress to something else, or someone would come in wanting something, and we would end the conversation without really reaching the point. Whereas Lopon Tenzin Namdak would stay very focused on what you were asking.

Would you say that spending so much time together created a bond, a closeness, a friendship?

I don’t think so. I was there to do research, and they were very happy about that, because they wanted people to know about Bön. For that reason they were happy to answer my questions. I think my attitude was one of deep respect for both of them and their achievements. But I don’t think we connected on a deeper personal level.

We did keep in touch afterwards, more with Abbot Sangye Tenzin than with Lopon Tenzin Namdak. Lopon was always so concentrated on his work and his teaching that it didn’t feel quite right to seek an ongoing exchange with him after I left. Also, I am not a practitioner. I told them both at the beginning that I was a Roman Catholic. They were very accepting of that. They had had contact with Catholics before; they had visited Catholic monasteries when they were in the West.

Did you go back to Menri after that?

I went in 2024 for the Mendrup ceremony. It was amazing to see how many changes had taken place in the monastery, the settlement and the school. The monastery has grown up! I wasn’t there long enough to really find out what all the monks and geshes were doing.

Before that, I had gone only once, in 2007, just for three or four days. My daughter was in India, so we met and went together. By then, Lopon Tenzin Namdak had left and was already in Nepal, but the abbot, Sangye Tenzin, was there.

You went to the celebration of Lopon Tenzin Namdak’s hundredth birthday last year – we met there. Did you meet Yongdzin Rinpoche on that occasion?

I didn’t ask for an appointment, to be honest. The number of people there wishing for contact with him was overwhelming. I didn’t put myself forward for a private meeting. I was simply happy to be there. I could see him from a distance.

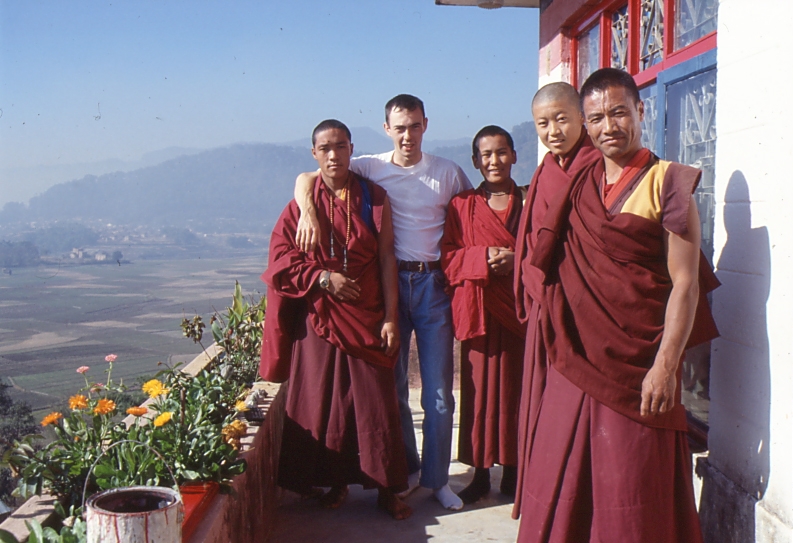

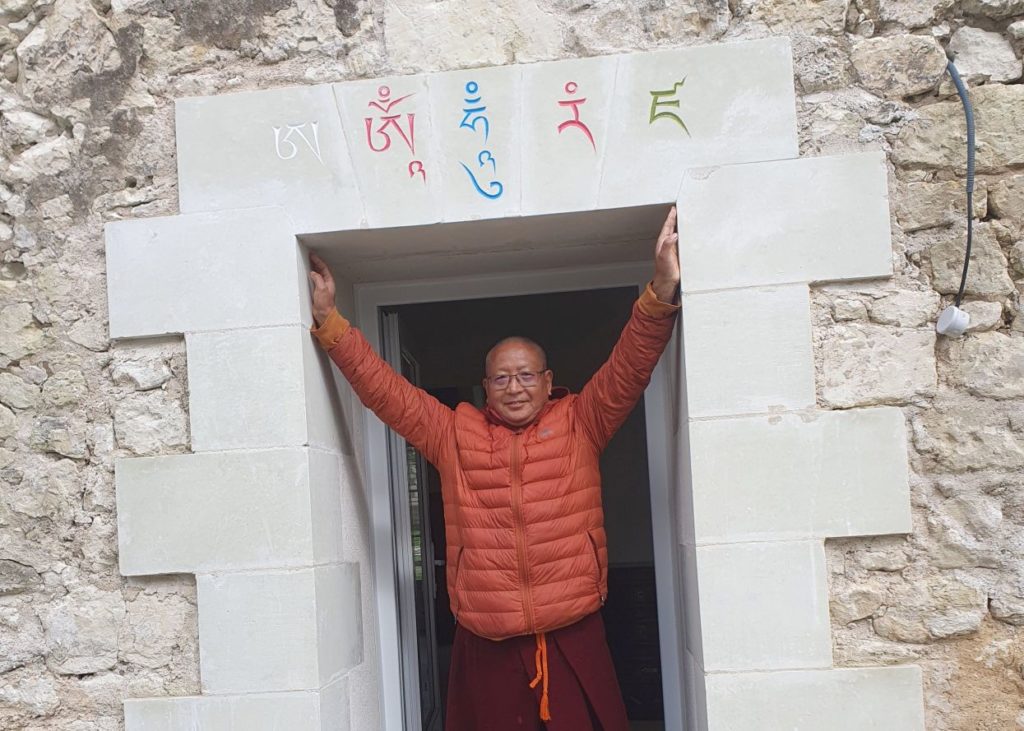

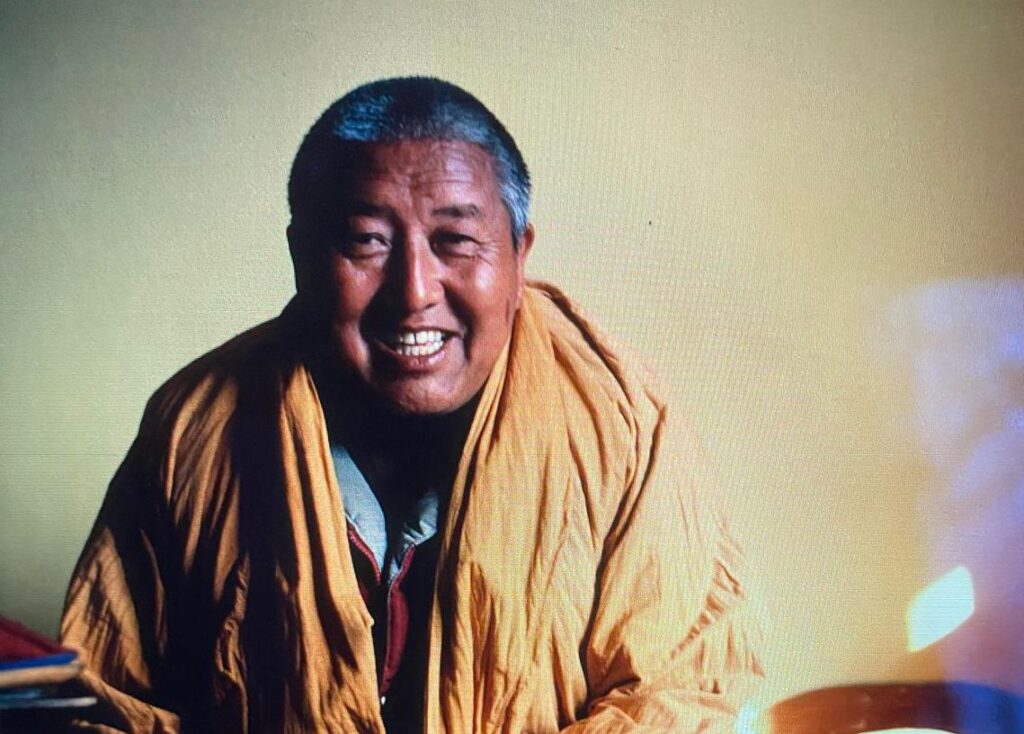

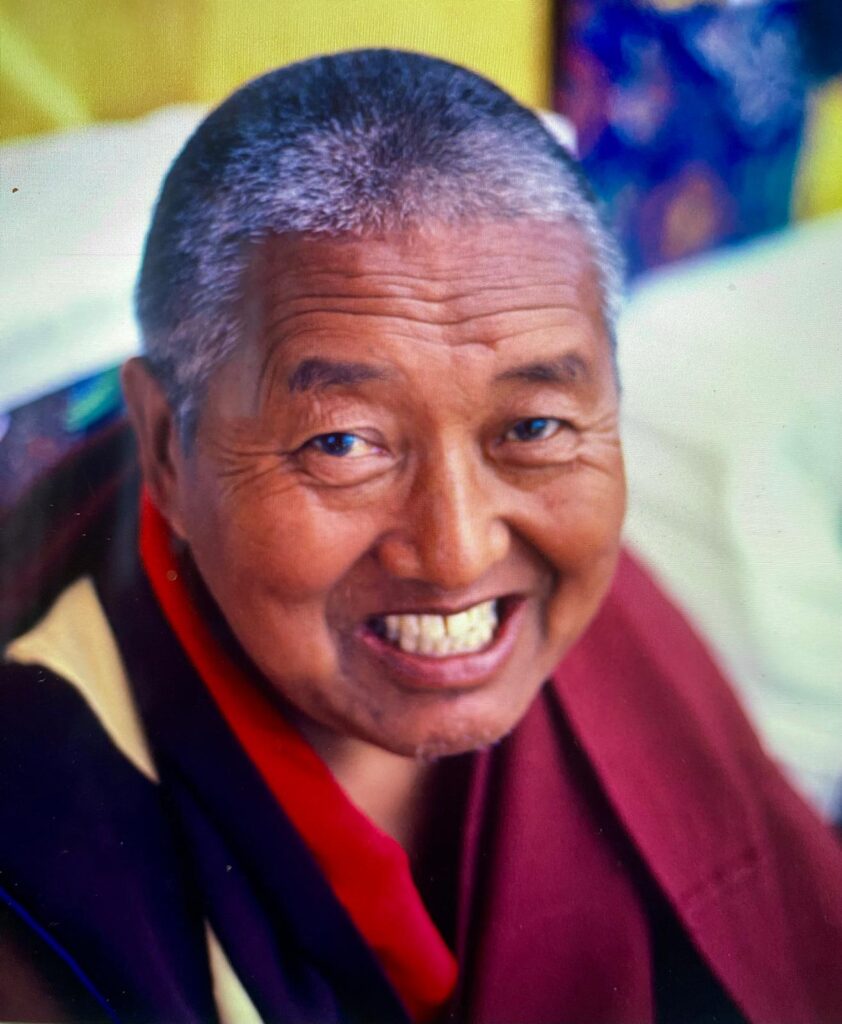

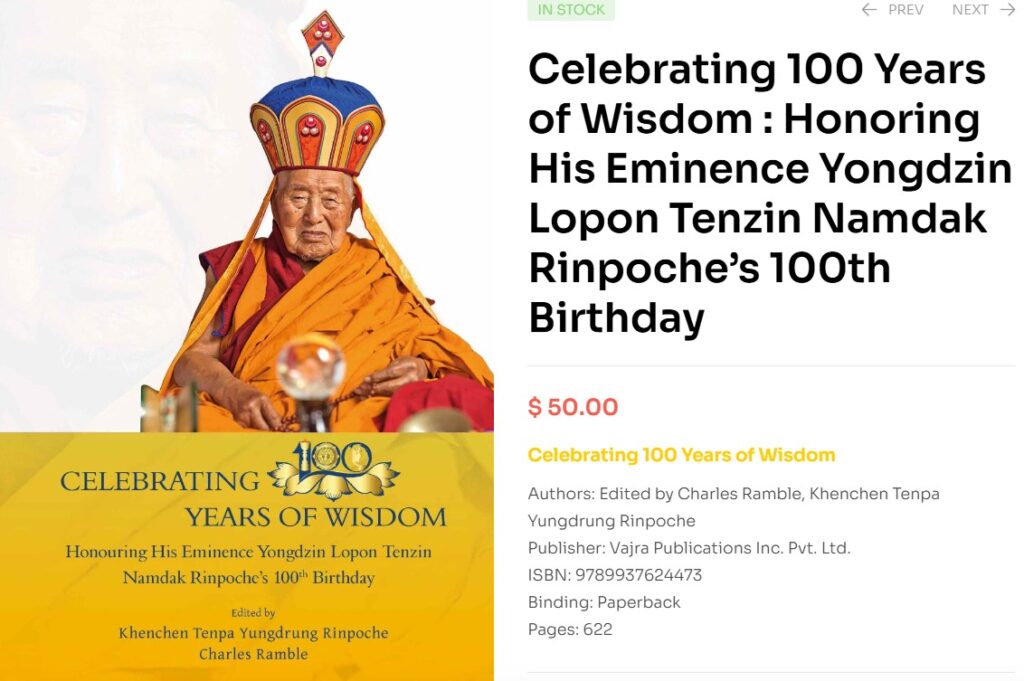

You took very good pictures while you were in Dolanji for your research. They accompany the article you wrote for Celebrating 100 Years of Wisdom, the collection of texts published for Yongdzin Rinpoche’s hundredth birthday. One photograph of him is particularly striking, the one which is the title picture of this article.

It’s really him: his lovely smile, his soft eyes. He was such a kind person. And you know, he was laughing quite often. He laughed a lot.

After your thesis was done, did you continue exploring Tibetan culture as a researcher?

I had a long break. Life took over. I have three children. So, I didn’t really continue with it. I attended a few conferences, wrote a few conference papers, and that was it. It is only since last year that I have begun to come back to it. When I was in Kathmandu, a friend recommended that I go to Vajra Publications and talk to them about my thesis of forty years ago. I went, and they agreed to publish it, so it may be coming out. I need to update certain parts and write a new introduction, so it will take some time. I am also planning to process some of my other research. I am finishing my work at the university in an administrative job, and after that I want to spend more time on my research.

Pictures of His Eminence Lopon Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche: Krystyna Cech