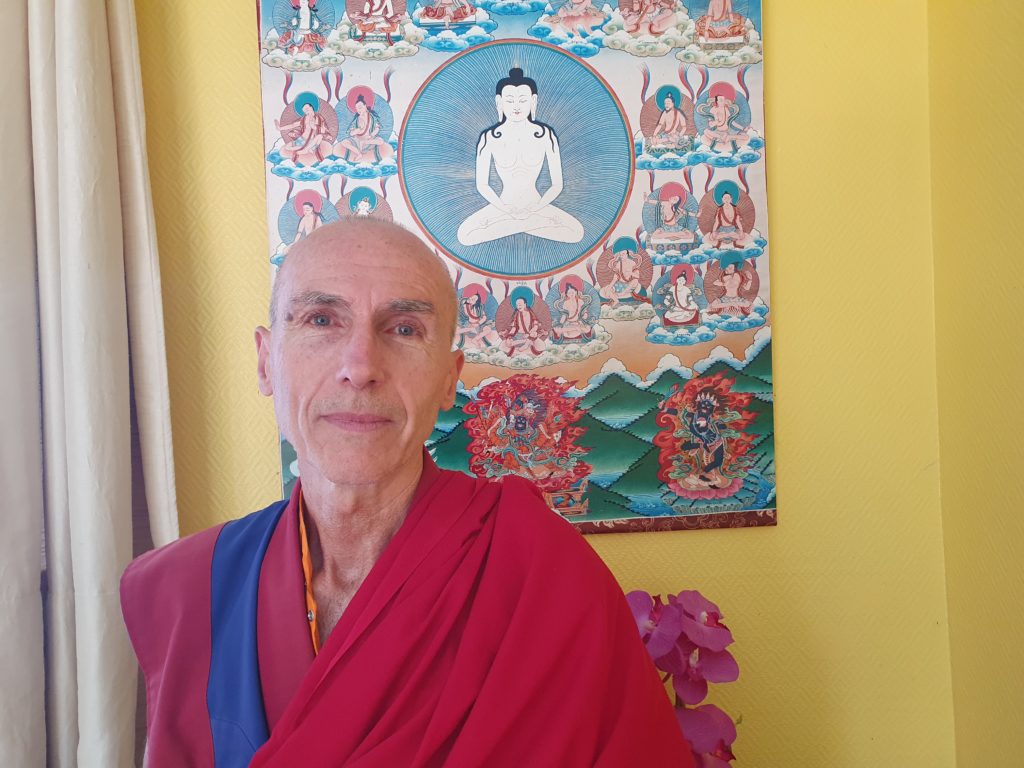

As a monk I have a great freedom, Dominique Troulay alias Yungdrung Tenzin says

This is a second part of an interview Yungdrung Tenzin gave us during the last summer retreat at Shenten Dargye Ling. After talking about his experiences as a translator of the teachings which take place at Shenten and online, we asked him what it is like to be a monk, about his connection with His Holiness 33rd Menri Trizin and whether he has anything to regret.

Dominique, how long have you been a monk in Yungdrung Bon tradition, with the name of Yungdrung Tenzin?

Since October 1999. It has been 23 years. My previous life seems to me a bit like a dream now, very different from the way I live now. And I am quite happy to be a monk because I have a great freedom.

In which sense? People usually associate the monkhood with the opposite, with less freedom.

Yes, it is true, but I feel more freedom. As a monk, I am free from all kinds of mundane engagements, which can be quite heavy, including a regular job.

How do you sustain yourself?

When I worked, I put aside some money and now I use my savings to maintain myself. This allows me to do activities that entirely support my practice. It also makes it possible for me to offer myself as a translator when Shenten needs me and I am happy to be of benefit. This is great freedom.

Also, I do not have children, so I do not need to work in order to maintain them. Being single also means that I take decisions individually and do not have to negotiate with anybody. This all simplifies my life and I can focus to develop my spirituality, I can practice. It is easier, as a monk, to live every moment as spiritual. A lay person has to deal with many worldly, distractive conditions and can easily forget about spirituality, pursuing mundane goals.

I know of at least two western men who became monks in this tradition and then disrobed. What in your opinion can lead to it and what has been instead the cause for your stability?

I had experienced all things of life before becoming a monk, I had my emotional life fulfilled, with my relationships, and I had exhausted a need or desire to have more of it. Perhaps some others took vows before being really ready, they were not fully satisfied, and this dragged them back. I also had had an interesting work, I went many times to the movies, discotheques and restaurants, so I could leave this all behind me with no regrets. I was satiated. When the monastic life was offered to me by His Holiness 33rd Menri Trizin, I was already forty one. If I had been twenty-five, I think I would not have accepted.

Now, I am really happy to be a monk. But who knows what will be. It can happen to anyone that he or she cannot or does not want to keep their vows anymore so I cannot guarantee that I will be a monk for my whole life, but for now, it is a condition that I really appreciate.

For many years, you were an assistant of His Holiness 33rd Menri Trizin and spent a part of every year at Menri Monastery. When did you start going there?

Well, I stayed there five months right after my ordination. Then my visa expired, and I had to return to France. After that I was coming every year, for seventeen years, until His Holiness passed away, and always for several months.

Was it necessary to spend some time in the monastery, in order to be ordained?

It was not. You can request the ordination to the abbot at any time, and he may or may not grant it, depending on the answers you give to his questions. If he feels that you are a proper candidate and you want to join the monastic life for correct reasons, he can ordain you the next day. But usually it is done on the occasion of an auspicious day, like a full moon or an anniversary connected with Tonpa Shenrab Miwo or some other important figure in Yungdrung Bon, such as Nyame Sherab Gyaltsen.

How many years did you follow Bon before deciding to become a monk?

Two years, not very long. You know, I would use a metaphor, it was like passing the narrow point of a sand watch. By different circumstances I was brought there, as a grain of sand, and I happened to arrive at a completely new life. My life´s circumstances converged to bring me there. And when His Holiness suggested to me to become a monk, I reflected about it for a few days and said yes, because it made sense to me.

You were close to His Holiness, being his assistant, didn’t you?

Yes, he was my spiritual teacher, he introduced me to some prayers, into meditation. But he was also very busy and so sometimes I did not see him for a month, even while being in the monastery. When I became his secretary, for English and French. I helped him write letters to westerners, and for that, we were almost in daily contact. We would sit next to each other, I would take notes on what to write. Sometimes he just sat next to me while I was typing the letter, without saying anything, reciting mantras. It was very special, the life I had with His Holiness.

A few months after I became a monk, he started to work on founding the nunnery at Menri. I went to see the site with him and other monks, and then I helped him with drawings of various buildings for the nunnery: the temple, the sleeping quarters, a medical school… I had been an industrial designer in my previous life and so I was able to make all the technical drawings he needed. I also looked after the construction work when the complex was being built. I became a monk at the moment when it was useful for Menri, I think. There was an amazing amount of building activity going on after 2000. When His Holiness passed away in 2017, all that he needed to build was finished. He had completed his mission.

When was the last time you saw him before he passed away?

I met with him in April and he passed away in September. I was at Shenten when I knew that he was not feeling well. I was told that he was in the hospital and then that he was out of the hospital and so I thought he was getting better. I should really have rushed to see him. I was waiting for a few days instead and then I applied for the visa but it took longer to obtain it and it delayed me furtherly… When I finally arrived, it was too late. This is karma.

On the other hand, your karmic connection made you spend so much time with him…

Yes, that´s true. His Holiness was my only contact at the monastery, in the beginning, and in general, he was my main connection there. I remember him every day. And we will see what happens. At the time of dying His Holiness may have connected with me…

His English was good enough, so that you two spoke together only in English?

Yes, he was able to express himself and that was not so good for my learning Tibetan. I did not have many contacts with other monks, very few of them spoke English. I did not make an effort to have a social life in the monastery. It seemed to me a bit like a contradiction to leave a social life in Paris and replace it with another kind of a social life in the monastery. For me, being a monk meant leaving behind that part of my life and staying more on my own. I did not make an effort to make friends with other monks.

Being on one’s own in the middle of a community is not the same as being somewhere in seclusion. Didn´t it make your life in the monastery a bit complicated?

It was frustrating at times, because I did not know what was happening. Sometimes I was very surprised that there was a ritual or something and I did not know about it. Or we had a holiday, and I did not know about it. Sometimes there was no food in the kitchen when I arrived to take it, and I did not know the reason. Many things like this. But this was my decision.

Do you regret not having learned Tibetan?

Yes, a bit. His Holiness did not push me in this direction and I had no real desire at that time to do so. If I really had worked hard when I was at Menri, building my language skills, I could have joined the dialectic school and I could have become a geshe. I could have explained to others rituals and teachings much better than I can do now. It did not happen and I have a different life now because of it. But this is not so important in the end. The most important thing is to realize the teachings. If I can embody the teaching, this would be the best.

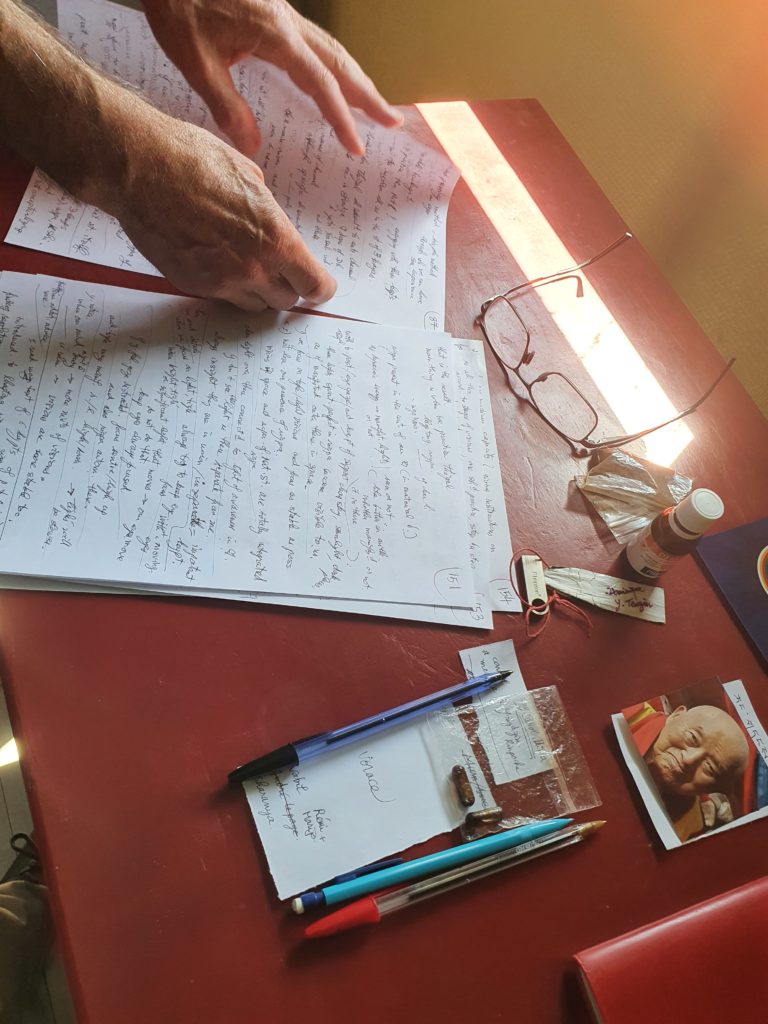

The notes are extremely important for me, I write down the maximum that I can of what the teacher says, almost every word. I want to be as faithful as I can. I feel this is a big responsibility, because what is explained is of great importance. Actually, I do not like having to write so fast, but this is the only way I can do it. My memory is weak, and I cannot keep in my mind a speech lasting sometimes several minutes. So I need to write these notes. I have written more than two hundred pages during the three weeks of the summer retreat. In the evening I go through my notes again.

From the first part of the interview. You can read it HERE.

What is the embodiment of the teaching, for you?

I am a dzogchen practitioner and, at the same time, I have to keep my vows. Which means to lead a very modest life, but from the highest perspective.

You are also very connected to Shenten Dargye Ling and to Yongdzin Rinpoche, you have come and stayed for teachings for many years…

Yes, I met His Holiness Menri Trizin in 1997 and Yongdzin Rinpoche one year later, in 1998. There was a bit of discomfort within me about who I should consider my root master, as if I had to choose between one of them. But maybe I did not have to. Anyway, Yongdzin Rinpoche introduced me to the natural state, and so I probably consider him my root master, and His Holiness is my other great master. I also have a very strong connection with Khenchen Tenpa Yungdrung Rinpoche. He is very kind to me.

Now I hope to make the best out of all those favorable circumstances, of being close to these great masters, listening to their teachings, translating them and putting them into practice.

Pictures: Jitka Polanská