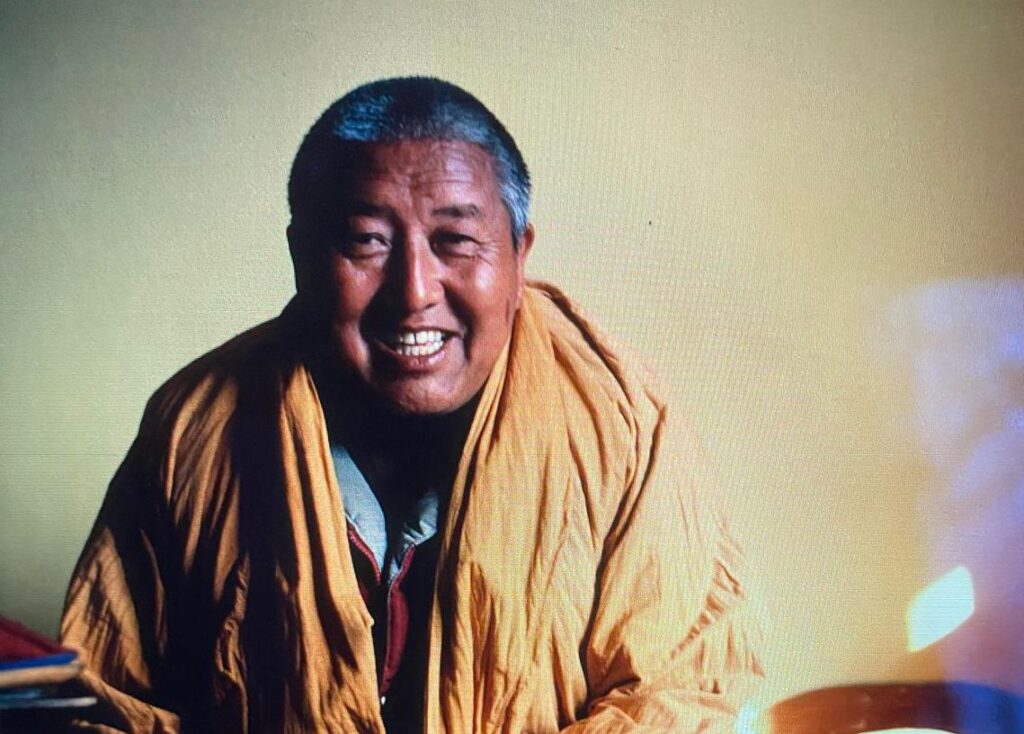

I follow in the footsteps of my teachers to preserve Bön culture, says Khenpo Lungrik Nyima from Ladakh

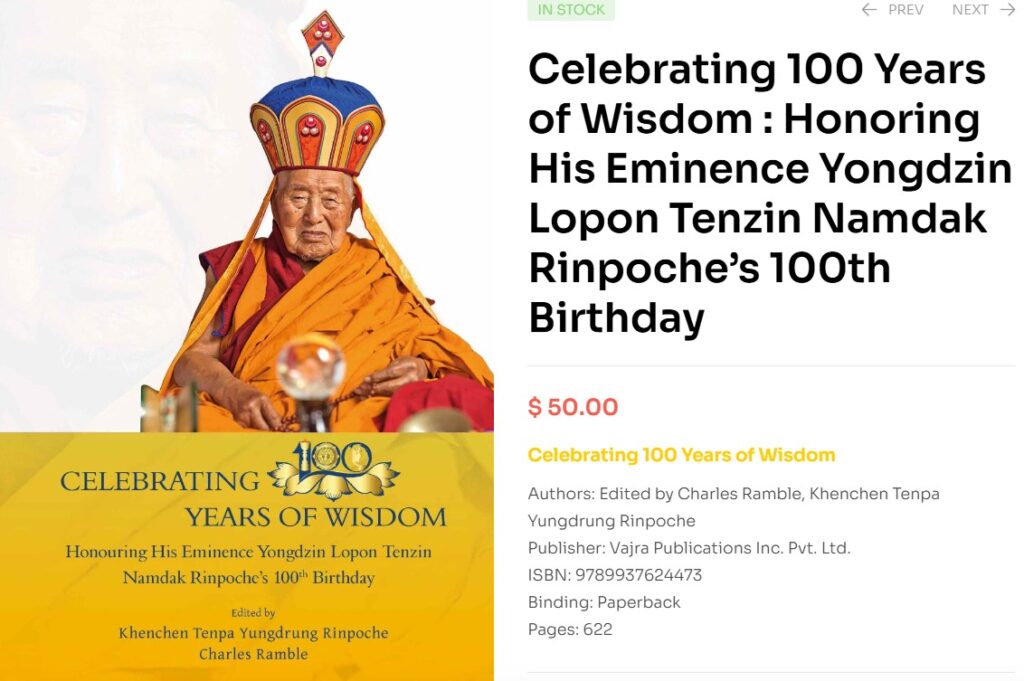

Khenpo Lungrik Nyima was born in Ladakh and returned there in 2000 to support his community. In this interview, he explains the purpose and activities of the center he leads. The interview was conducted by Jitka Polanska, Anna Sehnalova and Wolfgang Reuter in Kathmandu in February 2025, during the centenary celebration of the birth of His Eminence Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche.

Khenpo Nyima, you are originally from Ladakh, aren’t you?

My mother and father came to Ladakh from Tibet as refugees. My mother was from Ngari Prefecture, near Mount Kailash. My father is from Nagchu in Kham. They met and married in Ladakh. I was born there, and so were my brothers and sisters. I have four sisters and five brothers. We are ten siblings.

What did your parents do in Ladakh to make a living?

My family was mainly nomadic. We had yaks, sheep, and goats when I was a child. In 1990, the family moved to Choglamsar, a large Tibetan refugee settlement about eight kilometers from Leh, the capital city of Ladakh. There, they could not keep animals anymore.

Tibetans who live in the settlement live usually on some kind of business. Some open a small restaurant, many sell sweaters in the winter, this is what Tibetans who live in India mostly do. Some work as tourist guides in the summer, taking visitors on tours with horses. Or they cook for people who go on pilgrimage.

Does your family still live in the settlement?

Yes, my parents and some of my brothers and sisters still live in Choglamsar. One brother became a teacher of traditional Tibetan arts at the Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies in Varanasi. Another brother moved to Switzerland.

Were your parents Bonpo?

Yes. My mother followed both the Nyingma tradition and Bön. My father was a Bön follower.

In 1994, the Bön cultural center in Choglamsar was opened. Whose initiative was it?

It was initiated by some local senior people. They built the first construction, which served as a committee hall, a big room designed for all kinds of gatherings. It was built next to the river Indus that passes through the settlement.

You were at Triten Norbutse at that time, as a newly graduated geshe, and worked as a teacher there. Tell us more about your life before you returned to Ladakh. You studied at Menri Monastery in India, right?

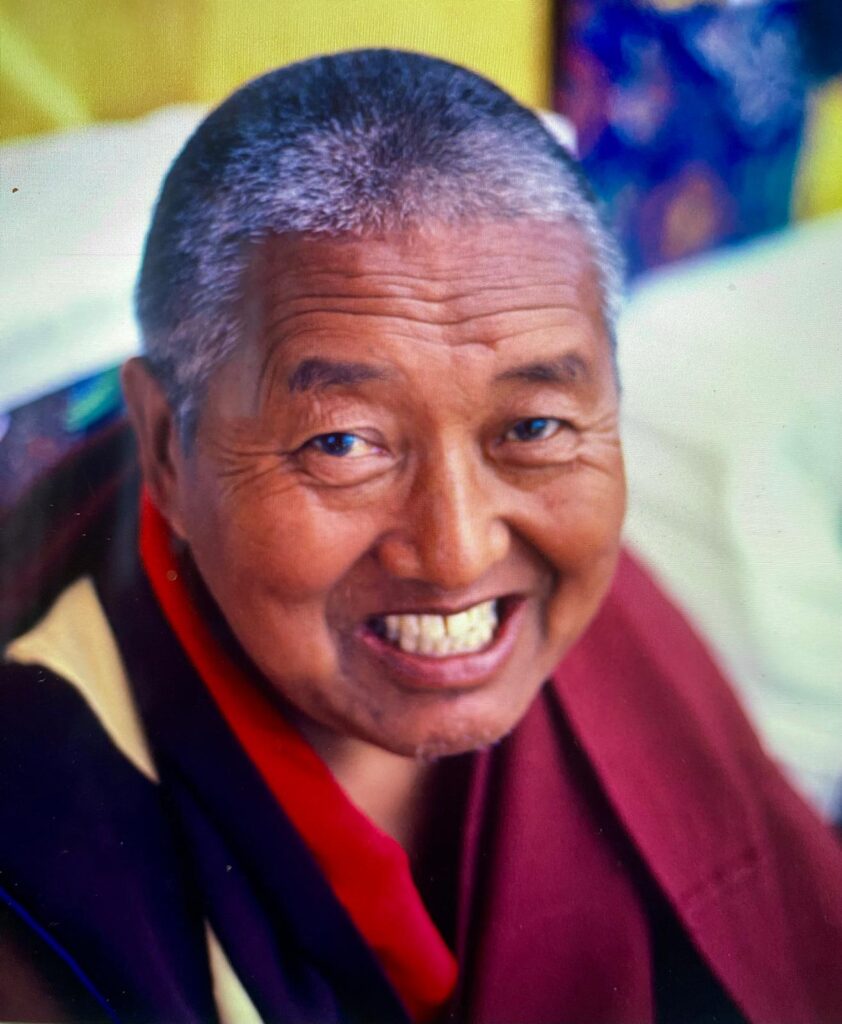

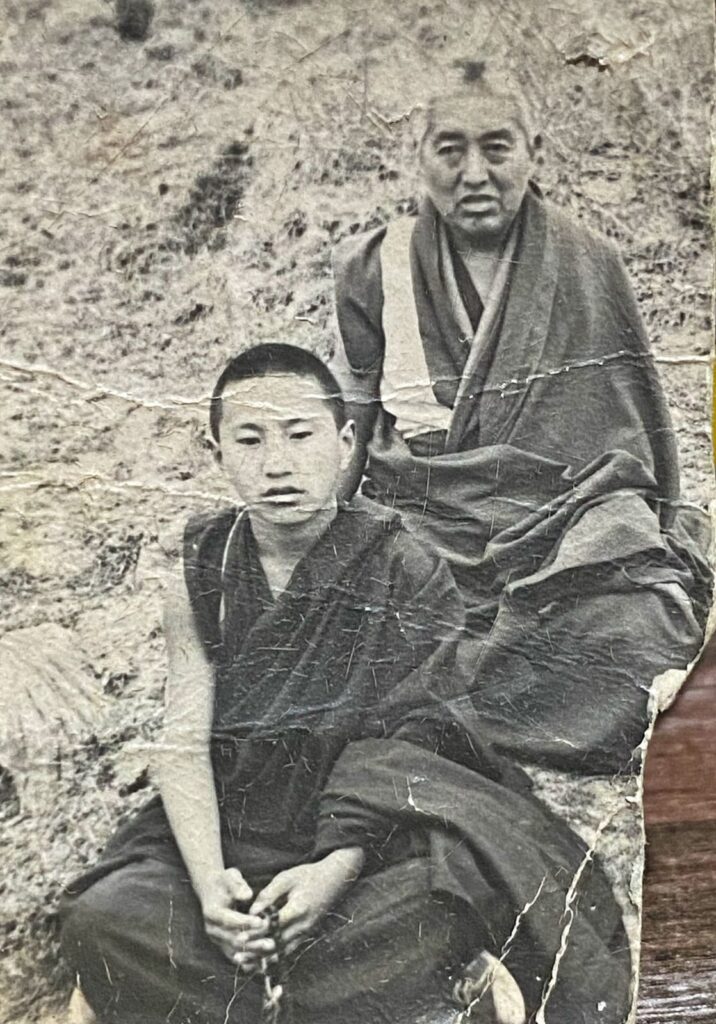

I was ten or eleven years old when I became a monk. I liked it; my parents did not force me. Before that, I studied Tibetan a little with my father. He tried to teach me the alphabet, but I did not learn much. Then my parents brought me to Menri Monastery. They stayed with me in Dolanji for a year. By the way, my father was a close Dharma friend of Yongdzin Sangye Tenzin, the teacher of my teacher Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche. They went together on a pilgrimage to Kongpo Bönri, which is a very holy place for Bönpos.

After a year or so, my parents left and went back to Ladakh. Originally, they might have planned to move to Dolanji permanently, but it was not easy to find work. They had been nomads for most of their lives and did not know English or Hindi. Knowing Hindi is important for any business they could eventually do there.

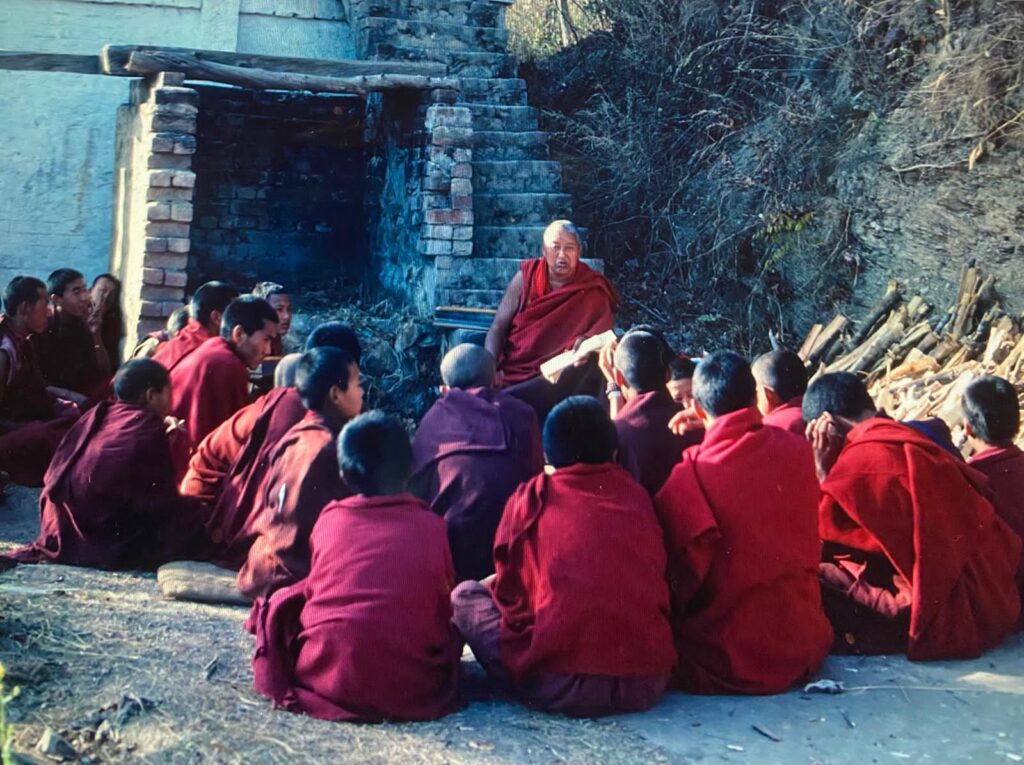

So they left Dolanji and I stayed in the monastery. I studied the alphabet again with the 33rd Menri Trizin. We were around twenty little monks. We studied early in the morning. Around eight o’clock, the other children went to school to receive modern education, but I was not interested in it and stayed to study Tibetan and some prayers with Rinpoche. Later I joined the Dialectic School and became a geshe in 1992.

Then you left for Triten Norbutse…

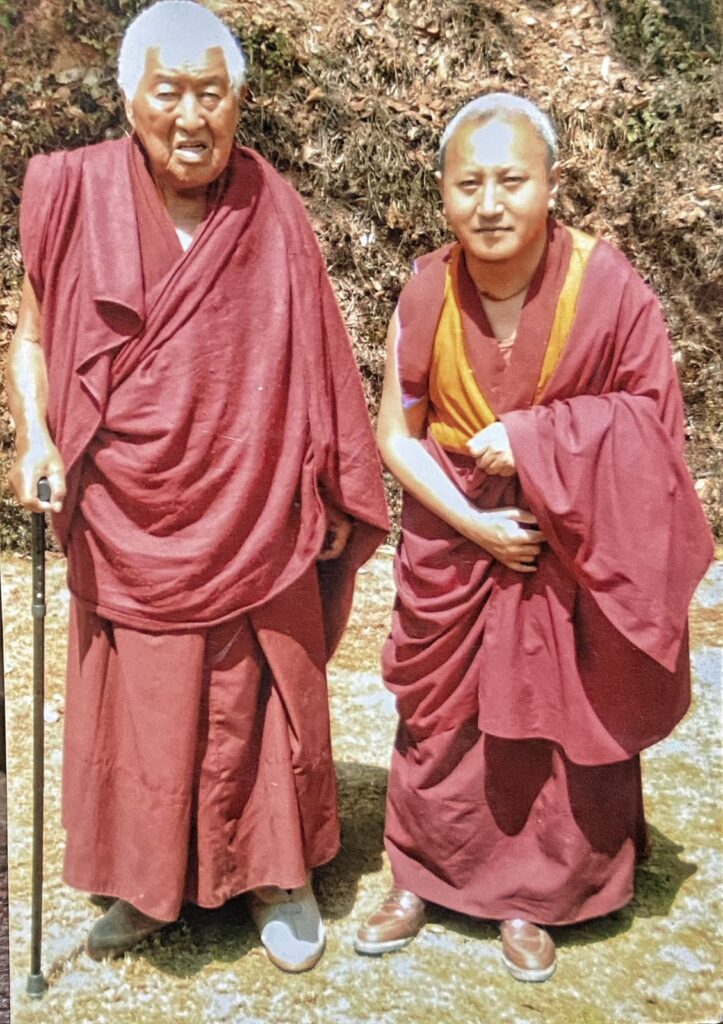

Yes, I decided to go there to join Yongdzin Rinpoche and study Dzogchen with him. I practiced Dzogchen meditation at the monastery together with Khenpo Nyima Wanggyal and Lama Sangye Monlam; we were one group. I also taught monks poetry, creating mandalas, and similar subjects. For a few years I served as a gekkö (master of discipline). But I mostly gave advice to monks; I was not strict.

Why did you go back to Ladakh?

It was upon the request of the 33rd Menri Trizin, Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche, and also some people in Ladakh. They insisted: “If you do not stay here, we will disappear,” they were saying. So I returned, it was in 2000. I was thirty something years old.

You are the only Bonpo geshe from Ladakh, aren’t you?

That´s correct. So, I went back, but with no experience of practical life, I had no idea how to build a center or what to do. I had lived in a monastery all my previous life. First, I tried to fundraise money. I went to other places in India—Dehradun, Sikkim, Dharamsala—and asked for donations, but I collected only one hundred rupees, very little.

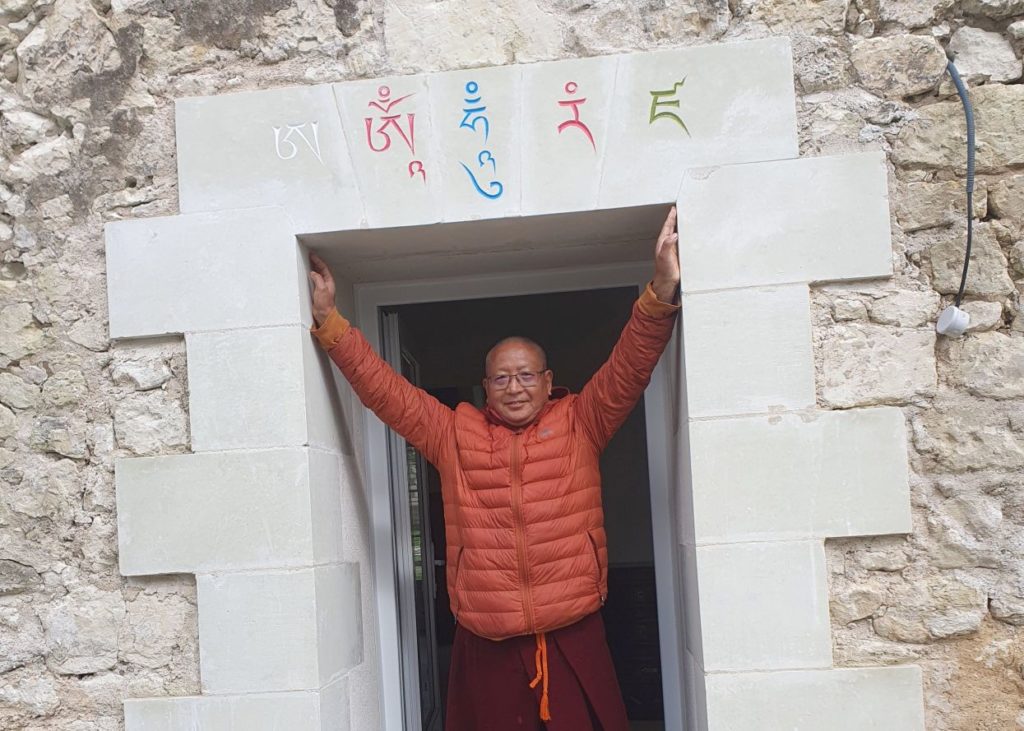

But slowly, slowly, we built our gompa, our temple. In 2002, the first floor of it was finished. Now, besides that, we have a building with four rooms. Before, everything happened in the gompa: guests stayed there and meetings took place there. Now we have a guest room and a kitchen. We are also building a bigger library—before we had only a very small one. My plan is to build a meditation place in a more remote area. A meditation place is important for anyone who wants to practice. Our place is close to a highway, it is quite noisy, so we need to build it a bit further.

What are the main activities organized by Bön Culture Preservation Society under your guidance?

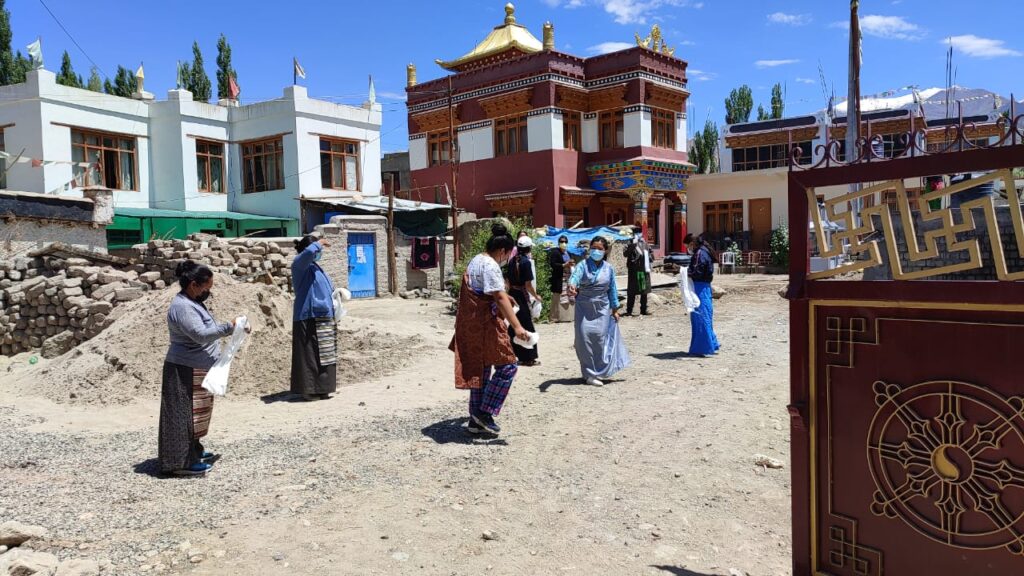

The main purpose is to keep and transmit Bön religion and culture as the root culture of all Tibetans. Children from Bönpo families, but also from Buddhist families come to the center to learn Tibetan, reading, writing. They go to the village school, and they are not taught Tibetan language or culture there. During vacations, especially winter vacations, they come to the center for a few hours every day. Those who are interested and come from Bönpo families I teach about Bön and Dharma, some prayers too.

Besides that, sometimes researchers come and ask questions. They are mainly students from the local university, but also foreign researchers drop by. Last year, Muslim students from Ladakh came to me. By the way, I also have a Muslim friend who is a teacher; he often comes. His ancestors followed both Islam and Buddhism. Mixing of religions is quite typical for Ladakh.

Is your center a monastic institution?

Not really, we are only two monks there. The other people who take care of the center are lay practitioners. On special days, like full moon days, we do a puja and read sutras. We do long-life prayers for His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and also for His Holiness Menri Trizin.

In 2024, you invited His Holiness the 34th Menri Trizin to Ladakh. What was his program there?

Yes, finally we could do it. Rinpoche stayed for one week. For that occasion, other lamas gathered too. Fifteen monks came from Triten Norbutse and more than twenty monks from Menri. Some families from Dolanji, the village connected to Menri Monastery, also came. Many gesheswho could not come supported me with donations. The lamas performed the consecration of our temple, and Rinpoche gave initiations to people. I think it was the first time in history that a Menri Trizin came to Ladakh. It was important for Bönpo families to receive his blessing.

We also invited other Tibetans, non-Bönpos, to Rinpoche’s talk. Two to three hundred people came to our event. There is not much information about Bön as a source of Tibetan religion and culture. This was an occasion for people to understand it better. We also invited representatives of the settlement, of the Union Territory of Ladakh, and the head of the Ladakh Buddhist Association. In the past, Bön was seen negatively in Ladakh, as in other places. Now it is quite okay. There are no big troubles.

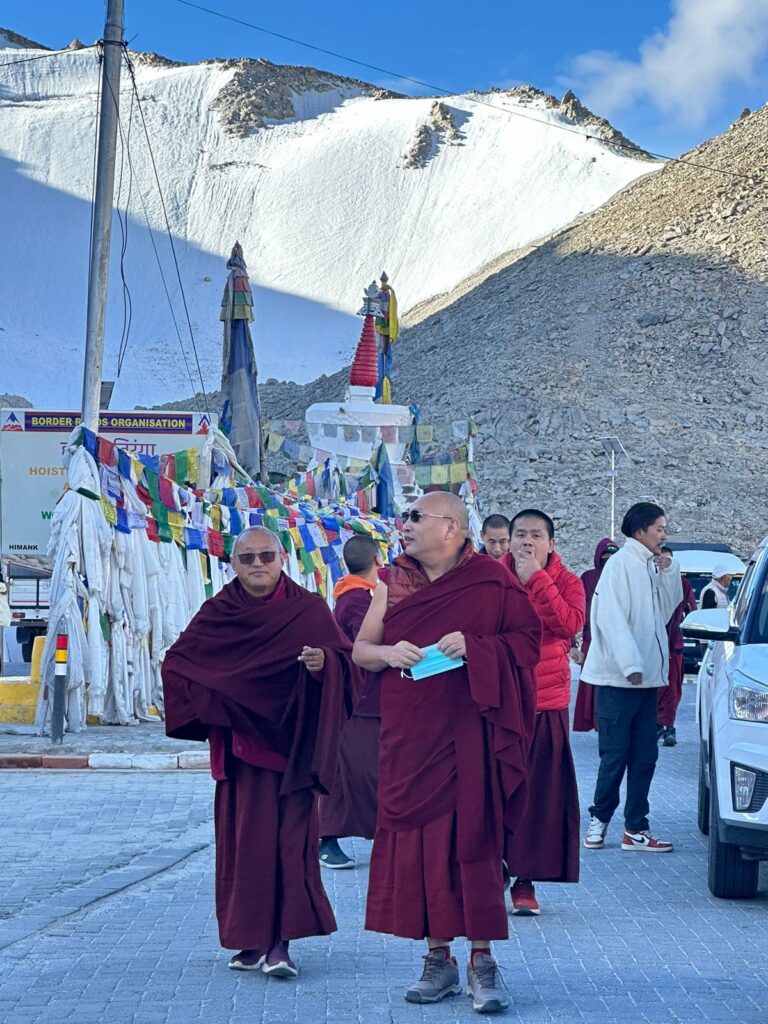

His Holiness Menri Trizin also visited some holy places in Ladakh, like Pangong Tso, a lake with salty water. It is a very famous place. We went with him to see the highest motorable pass in Ladakh, Umling La, and we performed sang chöd there.

Ladakh was a part of the Zhang Zhung empire before the seventh century, and researchers discover traces of Zhang Zhung culture here, mainly rock art. There is some evidence that in Zhang Zhung the anticlockwise movements were common in the rituals which is something that Bönpo rituals have as well.

Do you plan to offer monastic education at your center, to train young monks?

I cannot take care of young people who would like to become monks. You have to provide everything for them, and I cannot do that. But I would like to organize more Dharma teachings in the future—not only for monks, but for lay people too. Dharma is a medicine for the mind.

You carry out a large project with limited resources, and you are far away from your home monasteries. What helps you not to get discouraged when it feels difficult?

Sometimes I feel I am making very slow progress. Some other lamas can accomplish in two years what I do in twenty years. I am like a turtle—very slow (laughing). But I am steady and not discouraged. I came back to Ladakh following the footsteps of our root masters, Yongdzin Rinpoche and Menri Trizin, in their efforts to preserve our tradition and culture. I know it is the right thing to do. That makes me keep going.

Special thanks go to Kunga, a younger brother of Khenpo Nyima Lungrik, teacher of traditional Tibetan arts, who helped to check the interview and added some contextual information.

Researcher Anna Sehnalova (currently based at The Chinese University of Hong Kong) brings some context to the described initiative:

Khenpo-la is to be congratulated on establishing the first institution of Yungdrung Bon in the region of Ladakh in the Western Indian Himalayas. Unlike Nepal with traditional Bonpo communities in Mustang and Dolpo that go back many hundreds of years, India and the part of the Himalayan range there have historically not hosted prominent Yungdrung Bon communities that we would currently have substantial remnants of.

This changed with the influx of the Tibetan refugees into India since 1959. Among them were Bonpos, eager to save and practise their traditions. First came Menri monastery, originally established in Central Tibet in 1405 and in its exile manifestation near Solan in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh in 1969. It arose from the efforts of Tibetan Bonpo refugees led by Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak and is the first Yungdrung Bon monastery in the Western Indian Himalayas. Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak further foresaw the need for a large monastic stronghold of Yungdrung Bon in Nepal that would serve both Tibetan refugees and the historical Bonpo communities in the Nepali Himalayas, and established Triten Norbutse monastery in Kathmandu in 1987.

A second Yungdrung Bon monastery in India followed soon after Menri, already in 1974, albeit private and much smaller – Lingtshang monastery in Dehradun in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, again in the Western Indian Himalayas. It was a revived institution from eastern Tibet pursued by Trinle Gyatso from the nearby Lingtshang refugee settlement.

The Eastern Indian Himalayas gained their Yungdrung Bon monastery in the 1980s, namely Zhu Yungdrung Kungragling established by Yungdrung Tshultrim in the Indian state of Sikkim, historically an independent kingdom governed by hereditary kings adherent to Tibetan Buddhism similarly to Ladakh. Although the monastery was established locally, its administration fell under the exile Menri monastery.

Khenpo Nyima-la’s centre in Ladakh, a centre for laypeople and essentially a small monastic unit, is therefore the third Yungdrung Bon establishment in the western part of the Indian Himalayas. It testifies to the progress of the second exile Bonpo generation, being established by someone born in the exile and trained in the exile Menri monastery. Like most of the previous cases, its location aligns with a Tibetan refugee settlement, and reminds us how the Tibetan exile situation reshapes the religious landscape of the Himalayas. Without doubt, it constitutes a significant step for Yungdrung Bon.

Source: Karmay, Samten G. and Yasuhiko Nagano (editors). 2003. A Survey of Bonpo Monasteries and Temples in Tibet and the Himalaya, Bon Studies 7. Osaka: National Museum of Ethnology.

Anna Sehnalova, an anthropologist and Tibetologist, has spent several years in Tibet and the Himalayas engaged in studies and research, along with pursuing doctorates at Oxford University and Charles University in Prague. She is primarily interested in how people understand and relate to their ecological surroundings. She explored this, for example, through the Bonpo medical tradition and the Mendrub healing rite (writing a PhD thesis on the subject) or by looking at how Tibetan mountain deities are understood—a topic she discussed at the most recent International Conference of Bon Studies, held at Triten Norbutse monastery in February 2025.