Éducation, valeurs, dignité ! Une école où la modernité se mêle à la tradition

Lorsque les familles des villages reculés des montagnes de l’Himalaya envoient leurs enfants dans un monastère, cela ne signifie pas nécessairement qu’elles veulent qu’ils deviennent moines. Elles le font parce que le monastère éduquera les enfants dans leur langue maternelle et gratuitement. Le fondateur du monastère de Triten Norbutse à Katmandou, S.E. Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche, a accordé un refuge à de nombreux enfants mais il a toujours pensé qu’il serait préférable pour eux d’aller dans une véritable école, une école qui leur donnerait une éducation moderne mais qui transmettrait aussi les valeurs traditionnelles significatives de leurs communautés. Voici l’histoire d’une telle école.

(l’article original en anglais est ICI)

Les dures conditions climatiques, la pauvreté, le manque d’infrastructures, d’éducation et soins de santé – tout cela rend la vie des personnes qui vivent dans l’Himalaya difficile, voire douloureuse parfois. Des communautés parlant des dialectes tibétains ont vécu dans les montagnes pendant des siècles, mais aujourd’hui, toutes les familles qui en ont les moyens envoient leurs enfants dans des pensionnats éloignés pour les aider à avoir un meilleur avenir grâce à l’éducation. Cependant, beaucoup de ces pensionnats n’enseignent pas la langue et la culture tibétaines et les enfants grandissent déconnectés de leur langue maternelle et des traditions qui ont élevé leur peuple au fil des siècles. Ils peuvent même s’éloigner de leurs propres parents et de leurs proches.

Un grand nombre de familles ne peuvent pas se permettre de payer des frais de scolarité et gardent leurs enfants avec elles dans les villages. Mais, les écoles locales des régions de montagne ont un niveau d’enseignement très faible et ne font pas référence au contexte culturel et linguistique de la population tibétaine. Les enfants de ces familles vont probablement connaître le même cycle de difficultés et de lutte à vie que leurs parents.

Une autre option éducative pour les familles vivant dans les hautes altitudes de l’Himalaya est d’envoyer leurs enfants dans un monastère. Les monastères acceptent les enfants gratuitement et les éduquent dans leur propre langue. Toutefois, le curriculum monastique est axé sur les sujets traditionnels et sur les valeurs spirituelles et culturelles, et n’incluent pas d’éducation séculière moderne. En outre, la plupart des enfants ne sont pas enclins à aller dans un monastère.

Le monastère de Triten Norbutse, à Katmandou, reçoit fréquemment des demandes de parents qui souhaitent y accueillir leurs enfants. Son fondateur, S.E. Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoché, a donné refuge à beaucoup de ces enfants, mais il a toujours pensé qu’il serait préférable pour eux d’aller à l’école, une école qui leur donnerait une éducation moderne mais qui leur transmettrait aussi les valeurs traditionnelles significatives de leur communauté.

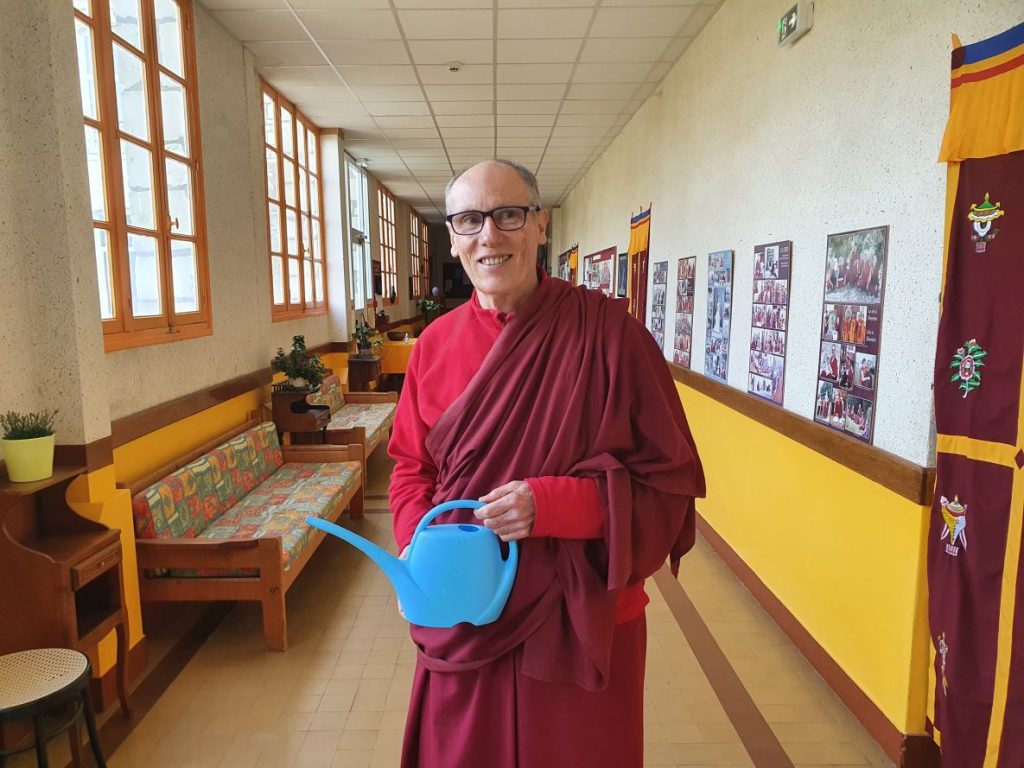

Le disciple de Yongdzin Rinpoché et l’actuel abbé de Triten Norbutse, Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung Rinpoché, a pris l’initiative de construire une telle école, qui est devenue sa mission à long terme.

Le choix d’un lieu

À cette fin, en 2007, la Sherig Phuntsok Ling Bon Society, l’organisation fondatrice de l’école, a été enregistrée au Bengale occidental, un État situé dans le nord-est de l’Inde. La même année, une parcelle de terrain a été acquise à Siliguri, la capitale du Bengale occidental. La ville a été choisie pour son accès relativement facile aux différents coins de l’Himalaya, étant proche de Sikkim, Darjeeling, Kalimpong, et à seulement quarante minutes de route de la frontière avec le Népal. Le Bhoutan n’est qu’à cent cinquante kilomètres de là et il faut moins d’une journée, en voiture, pour se rendre à Katmandou, où réside la communauté monastique de Triten Norbutse.

Un autre point fort est que Siliguri est très diversifiée sur le plan ethnique, culturel et linguistique. “C’est un melting-pot de la région et elle est devenue un important centre culturel. Nous avons pensé qu’elle pourrait offrir de bonnes opportunités d’éducation pour nos élèves, une fois qu’ils ont fini l’école”, dit Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung.

Il a fallu de nombreuses années avant que des fonds suffisants soient collectés et que la construction de l’école commence, en 2016. Les architectes d’une société basée en France, Architecture et Dévelopment, ont été impliqués dans la planification. Avec des professionnels locaux, ils ont conçu une structure respectueuse de l’environnement et résistante aux tremblements de terre. Des matériaux naturels comme le bambou et les pierres locales ont été utilisés dans certaines parties de la construction. Le premier bâtiment de l’école comprenait des salles de classe, une cuisine, une salle à manger et de méditation, une bibliothèque, des dortoirs séparés pour les garçons et les filles, plusieurs salles pour le personnel, un petit dispensaire, ainsi que des toilettes et des salles de bain.

L’ouverture de la nouvelle école a été annoncée grâce aux relations que l’équipe de l’école avait dans les montagnes. ” De plus, deux membres de l’équipe se sont rendus dans des villages éloignés et y ont diffusé la nouvelle “, explique Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung.

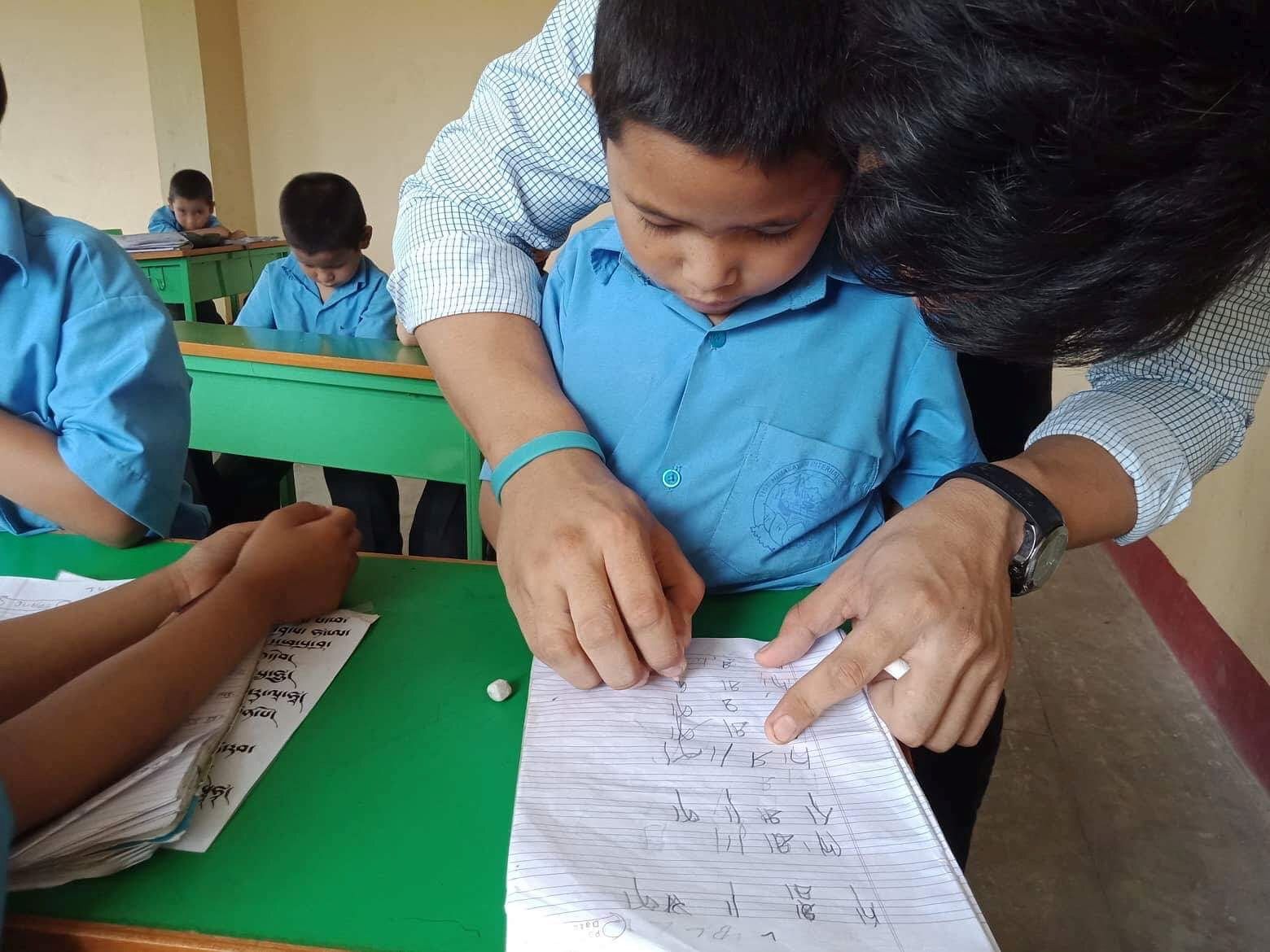

Ainsi, entre janvier et mars 2018, environ soixante-dix enfants provenant de différentes régions de l’Himalaya de l’Inde et du Népal sont arrivés et se sont installés dans le pensionnat. La plupart d’entre eux appartiennent à des familles économiquement et socialement vulnérables dont les valeurs et le contexte culturel sont ancrés dans le bouddhisme et le Bon, une ancienne tradition spirituelle très fortement présente dans les montagnes au cours des siècles passés. L’école est gratuite pour tous les enfants.

Tise Himalayan International School (THIS), comme l’école est appelée, a officiellement commencé avec quatre classes en avril 2018, lorsque la nouvelle année scolaire commence habituellement au Bengale occidental. “Tout s’est déroulé sans problème. J’ai été impressionnée par la bonne organisation”, déclare Christine Trachte de Yungdrung Bon Stiftung, une fondation allemande qui soutient l’école depuis le tout début.

La direction de l’école a été confiée au président de la Sherig Phuntsok Ling Bon Society, le Vénérable Sonam Norbu, qui, au cours des quatorze années précédentes, avait été responsable de l’auberge et de l’enseignement de la langue et de la culture tibétaines dans l’école de Lubra au Mustang. Au début, son équipe pédagogique de base comprenait un directeur et quatre enseignants. Deux d’entre eux enseignent la langue et la culture tibétaines.

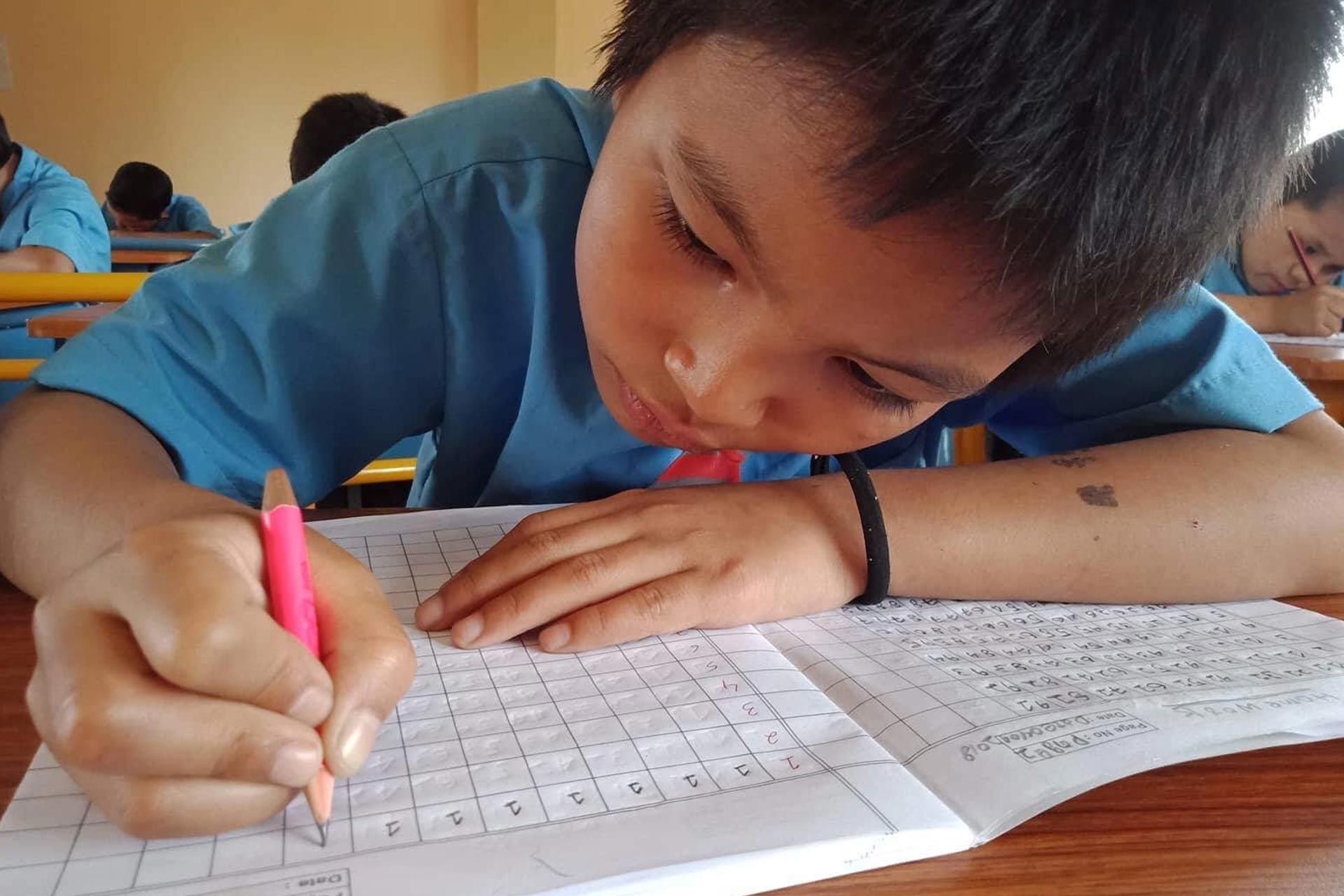

Le programme de l’école est tout à fait unique. Il répond aux normes éducatives requises par le gouvernement du Bengale-Occidental et le Conseil central de l’enseignement secondaire, mais il est enrichi d’éléments de l’art, de la culture et de l’histoire des régions himalayennes et met l’accent sur la conscience environnementale et le respect de la nature typiques de la spiritualité traditionnelle.

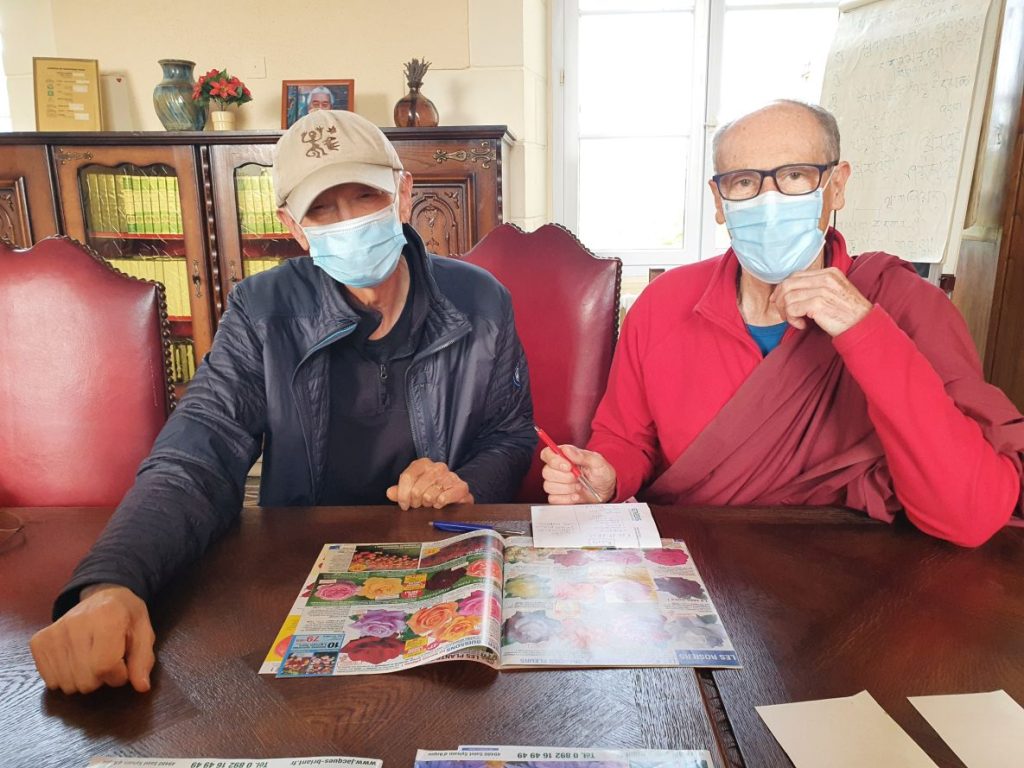

“Nous avons travaillé en étroite collaboration avec Khenpo Tenpa Rinpoché et Sherig Phuntsok Ling Bon Society pour définir la valeur ajoutée de l’école, en réfléchissant à la manière d’unir une approche scientifique rigoureuse de l’éducation et le riche bagage traditionnel de la culture himalayenne. Nous avons eu de nombreuses réunions à ce sujet”, raconte Mara Arizaga. Elle est l’un des fondateurs d’EVA (Enlightened Vision Association), une organisation à but non lucratif basée en Suisse qui se concentre principalement sur la préservation de l’héritage culturel de l’Himalaya et qui, depuis de nombreuses années, aide l’école de diverses manières.

L’école a une approche holistique de l’éducation, impliquant le corps, la parole et l’esprit des élèves dans l’apprentissage. Elle donne l’occasion aux enfants de pratiquer le sport et la danse, ainsi que le yoga traditionnel himalayen. Les élèves sont initiés à la méditation et sont naturellement exposés aux valeurs spirituelles traditionnelles que sont l’empathie, la générosité et l’ouverture du cœur.

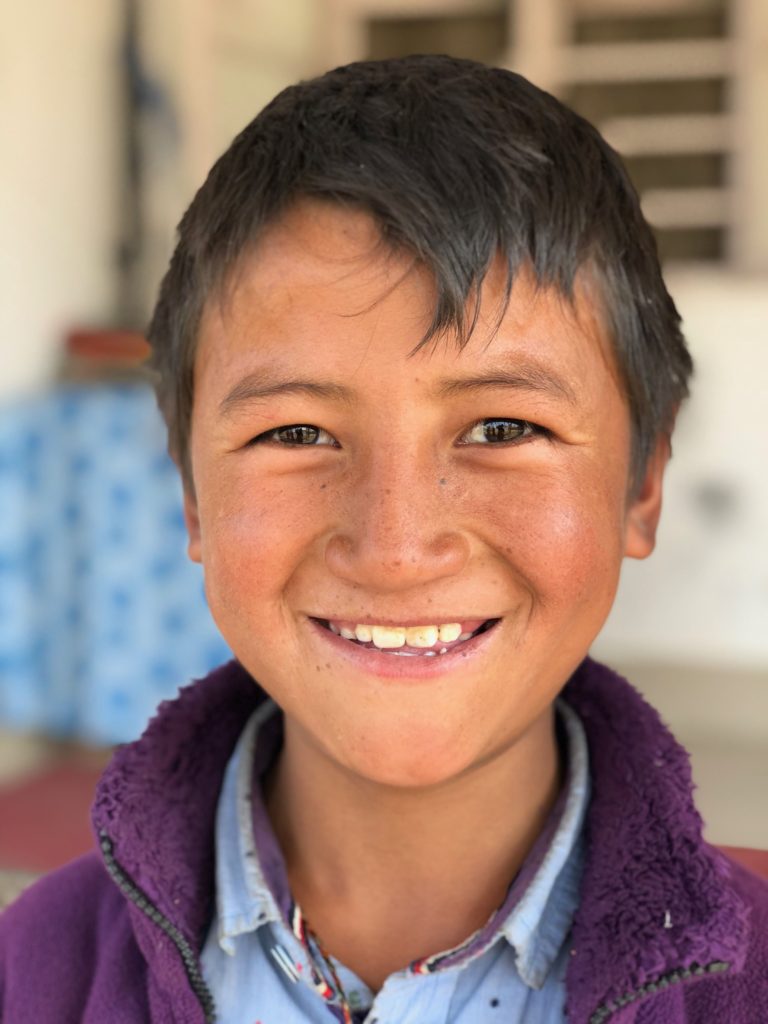

Un visiteur de l’école peut voir des enfants pleins de vie et de confiance dans un environnement chaleureux et coloré. Bien qu’ils soient éloignés de leurs parents pendant de longues périodes et qu’ils ne puissent souvent pas leur rendre visite, même pendant les vacances, ils savent que c’est l’occasion pour eux de montrer tout leur potentiel. Cela les aide à surmonter le mal du pays.

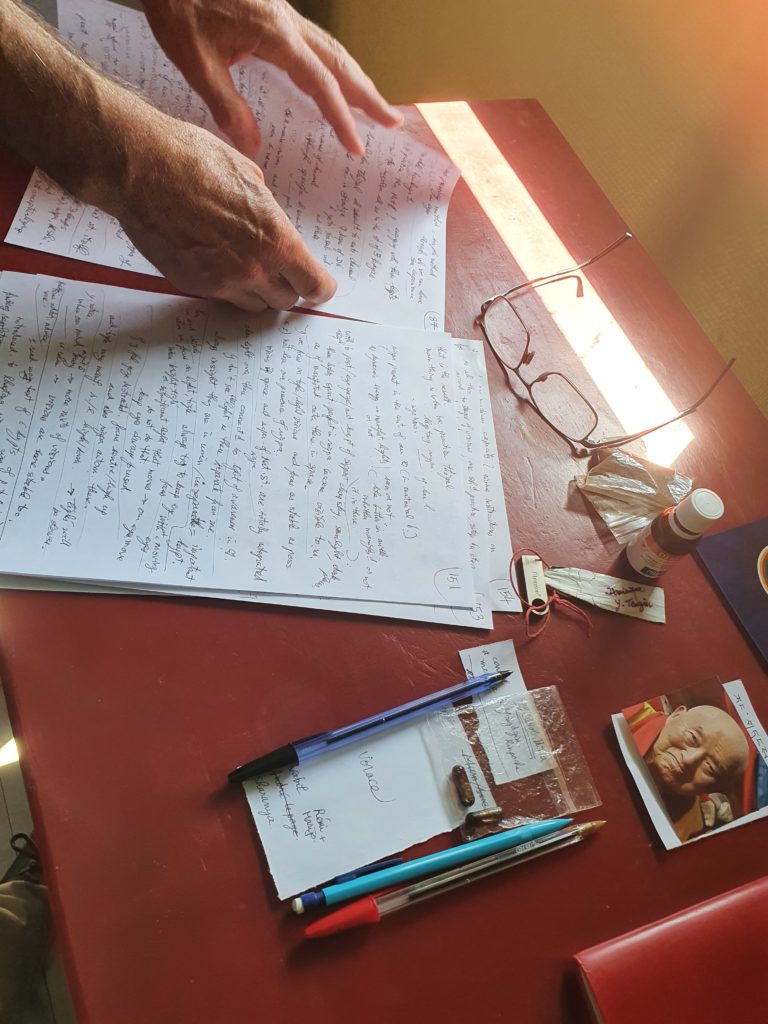

Afin de maintenir les liens avec leur terre natale, THIS a également produit ses propres manuels d’apprentissage du tibétain avec des histoires qui présentent aux enfants les personnalités, les montagnes ou les rivières des régions dont ils sont originaires. Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung a formé une équipe de personnes qui ont recherché et collecté ces histoires et créé des textes basés sur celles-ci.

Parfois, des parents viennent visiter l’école. Vieillis prématurément par le dur labeur, et ressemblant davantage à des grands-parents, ils sont visiblement émus de voir leurs enfants s’épanouir dans une vie dont ils n’auraient jamais pu rêver pour eux-mêmes.

La voie difficile

Actuellement, THIS compte sept classes et dispense un enseignement à 138 enfants, dont la moitié sont des filles. Promouvoir l’égalité des chances pour les filles est l’un des objectifs de l’école. Onze enseignants, une nounou et un cuisinier s’occupent des enfants. En outre, quatre membres de la société Sherig Phuntsok Ling Bon travaillent pour le bien-être général des enfants, gérant également l’administration de l’école et réalisant des projets liés à l’extension et au développement des bâtiments scolaires.

L’école ne reçoit aucune aide financière du gouvernement et ne perçoit pas de frais de scolarité, ce qui signifie qu’elle dépend entièrement des donateurs. Sa viabilité financière est un grand défi, mais Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung est intransigeant dans son objectif de maintenir le haut niveau de l’école. “Les écoles de charité comme la nôtre ne peuvent parfois pas offrir la meilleure éducation par manque de fonds, mais nous voulons être une école exceptionnelle quoi qu’il arrive”, dit-il. “Abaisser la qualité serait humiliant pour les enfants et leur dignité est très importante pour moi. Je veux que l’école leur donne la certitude qu’ils sont aussi bons que n’importe qui d’autre et parfaits comme ils sont”, affirme Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung.

Il est lui-même un donateur, donnant à l’école tout ce qu’il reçoit en tant qu’enseignant du dharma, et il travaille sans relâche pour augmenter les dons, envoyant des demandes de financement, suivant chaque opportunité qui se présente. Les personnes de la société Sherig Phuntsok Ling Bon, la fondation allemande Yungdrung Bon Stiftung et l’organisation suisse EVA le soutiennent dans ses efforts, tout comme d’autres organisations et individus. Pourtant, les fonds ne sont pas suffisants pour le moment. “Nous sommes toujours en équilibre sur le fil du rasoir”, déclare Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung.

L’une des priorités qu’il mentionne est d’augmenter les salaires des enseignants et de leur donner des contrats de travail plus stables afin qu’ils ressentent moins d’incertitude. Les salaires que l’école peut se permettre de verser pour le moment sont encore loin d’être attractifs.

Il est également urgent de finaliser la construction du deuxième bâtiment, une structure de trois étages commencée en 2020. Il contient quinze salles de classe, des bureaux et des espaces de travail pour les enseignants, ainsi que des toilettes. Plus de la moitié du coût a déjà été payé et l’entreprise de construction continue de travailler avec la promesse d’être payée lorsque d’autres finances seront disponibles.

L’école a également besoin d’un nouveau dortoir pour les filles afin de pouvoir inscrire davantage d’enfants, jusqu’à la pleine capacité de 300 élèves, 150 garçons et 150 filles, avec une moyenne de 25 enfants par classe, et 12 classes au total. L’école vise à couvrir un enseignement secondaire complet.

Enfin, à l’avenir, le souhait de Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung est de construire une petite clinique sur le terrain de l’école. Cet établissement de soins aurait une double fonction – prendre soin de la santé de la communauté de l’ école et aussi préserver et développer la science médicale traditionnelle de l’ Himalaya.

“Les connaissances médicales himalayennes et la tradition de respect de la nature ont peut-être un mot à dire dans le monde actuel qui est confronté à des déséquilibres et à une dégradation importante de l’environnement”, déclare Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung.

Il estime que l’école ne profitera pas seulement aux enfants, mais qu’elle aura également une influence positive sur le monde qui les entoure. “Où qu’ils aillent par la suite, quelle que soit leur carrière dans la vie, les valeurs qui leur ont été enseignées resteront avec eux”, pense-t-il.

Photos : archives de Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung Rinpoche, Jitka Polanská, Darek Sawczuk