Khenchen Tenpa Yungdrung: I am inspired to help those children

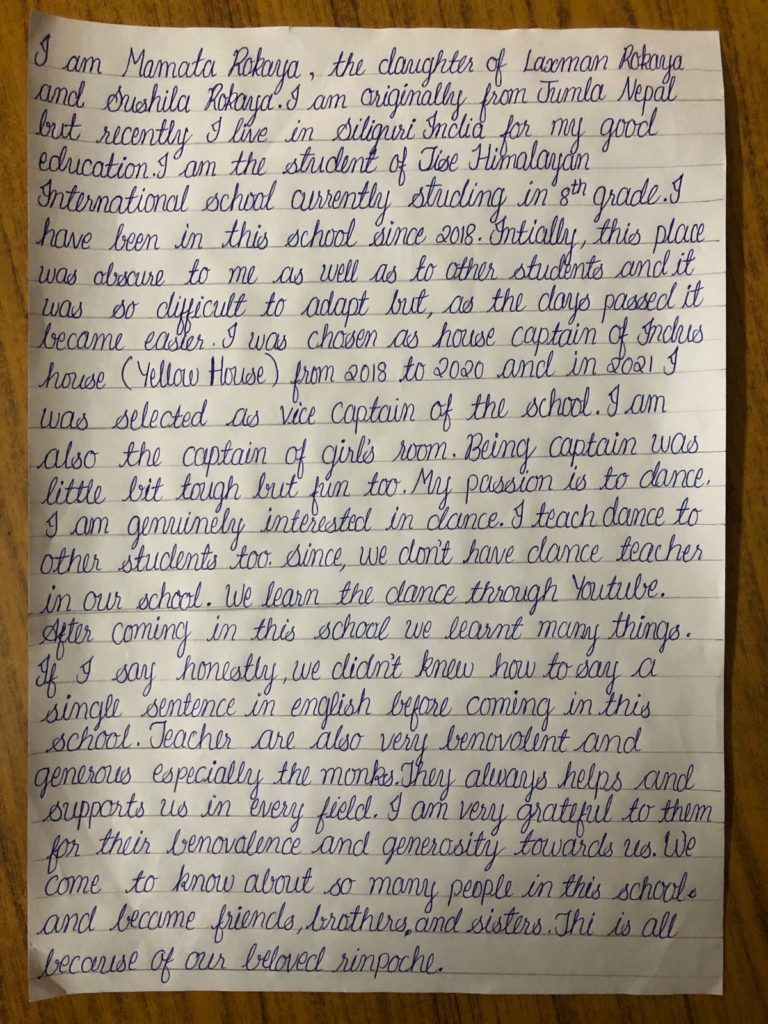

Many children in remote areas of the Himalayas will get poor or no education if they remain in their villages. Knowing this, Khenchen Tenpa Yungdrung Rinpoche, the abbot of Triten Norbutse Bön monastery in Kathmandu, had worked hard for fifteen years to create favorable conditions for building a school where such children can learn what will support them in their lives. Finally, Tise Himalayan International School (THIS) was born, five years ago. Currently, it hosts around hundred sixty students. “They are enthusiastic to learn and talented in many ways. It gives me strength and motivation to keep on going no matter how difficult it is to finance and run the institution,” Khen Rinpoche says.

You go often to the school, being the leader of the school’s team, and you have a chance to spend time with the children. What would you say about them? What do you see?

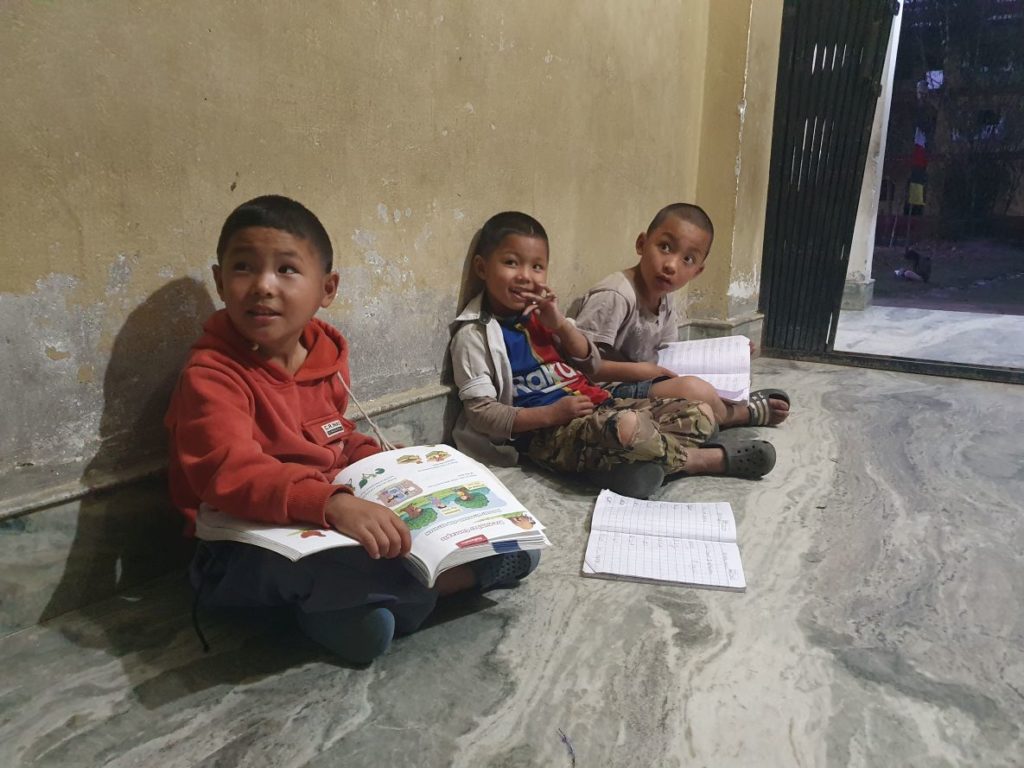

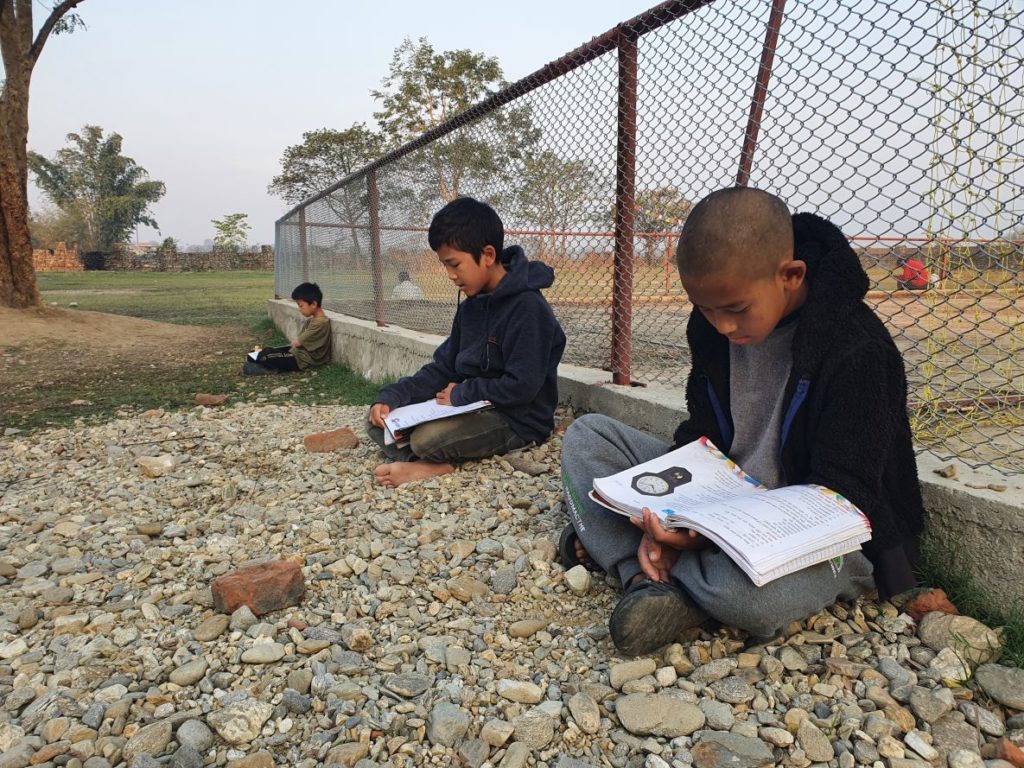

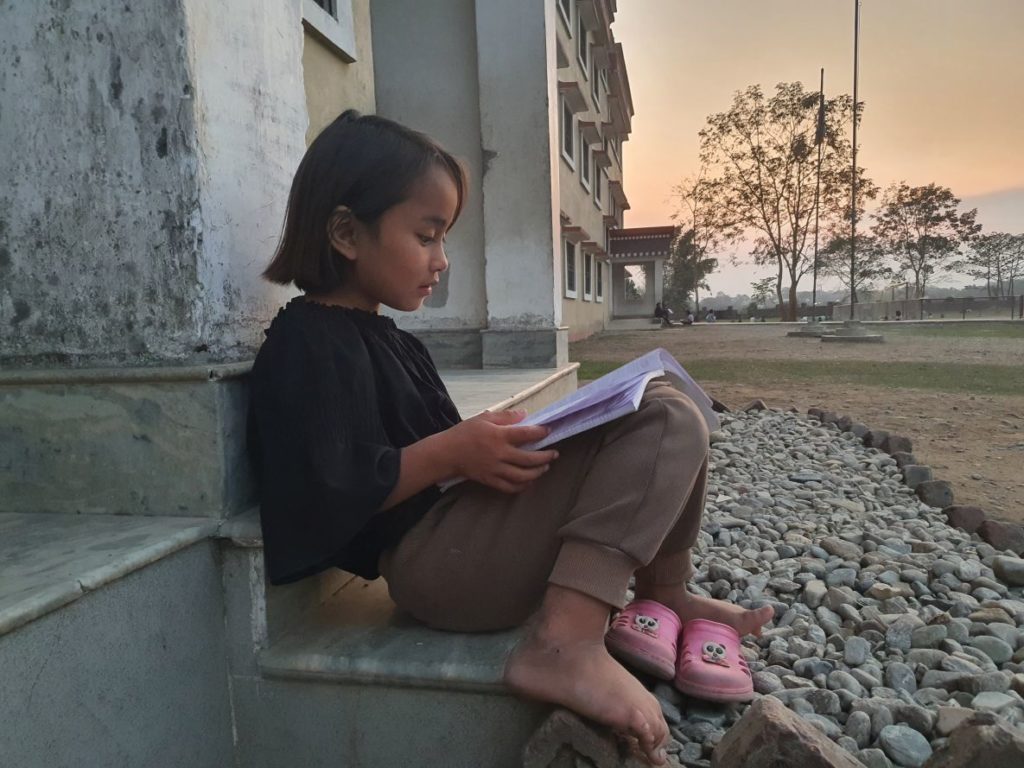

When I go there, I see happy, bright and healthy children enjoying themselves and willing to learn. Older ones can read and write in Tibetan, all of them learn Tibetan and English every day, as well as Nepali. They are inspired to succeed in the school subjects, and they like arts and sports. It is a pleasure to see them playing football or dancing. They are good at it!

How would you describe the material conditions of the school?

We do not have many things. As the children grow, I see more and more needs that are not fulfilled yet. Material conditions are modest. Of course, everything is relative. When a western visitor comes, they may see all poor and run down, but compared to some other “charity” schools we do well I think. And we constantly strive to do better. I wish that those kids had things that all children wish to have.

What are the things which are not there yet and would be necessary?

Better shoes and clothing, especially sports shoes, for example. Also, we would need to furnish our library with more books, maybe putting some board games too, we would like to buy a couple of laptops for the library. We do not have these things. We should improve the conditions for doing sports. At the moment there is a playground for football and that’s all. The children are very creative in playing with the little they have, they are very lively, but of course, I would like to give them more and they deserve more.

Teenage children also may need more personal space.

Yes, as the number of children grows every year, it becomes more and more urgent to expand the hostel. Our priority is to build a hostel just for girls and offer them a space more in accordance with their needs, with more privacy and comfort, while the current building would be used only by boys.

There is a plan to offer not only primary, but also secondary education at the school, altogether 12 grades. Why is providing good primary education (8 grades) or primary and lower secondary education (10 grades) not enough?

Teenage is a crucial period in education. Children should deepen their knowledge of Tibetan and get longer exposure to value education. If not, they may lose what they learned because it will not be stabilized.

What would you say about the teachers? Is it difficult to find and keep them?

Some of our teachers are there from the very beginning, which we appreciate a lot, continuity and stability are very important. As for now, we cannot pay high salaries but still, we receive applications from valuable candidates. Recently, we hired a science teacher, a math teacher and an additional Nepali teacher.

This year you admitted twenty eight new children, aged 5 to 9. They may seem quite many to be integrated at once. Many things will be completely new for them. Is it difficult for the school to manage that?

We received more than fifty applications from parents or guardians, our plan was to take in twenty, maximum twenty-five children, then we added three more children because they were weak and vulnerable and we did not want to leave them out. I think we need to go on this way, and I believe that the school can manage. We have a very good system of self-organization of children in the hostel, older children help younger ones, also two nannies and other staff are there for everyone. I think we can manage, but of course, I do not say it is an easy thing to do. And there are plenty of things we have to improve.

Now in April there is the fifth year´s anniversary of the school. What would you say looking back and what are your next steps and goals?

When I look back, I see lots of accomplishments done in those five years, children are growing and responding well to the teachings, they are compassionate and respectful, along with good progress of other subjects including English, they can read and write Tibetan quite well, of which they had zero knowledge when they arrived; they progress. In April we opened the eighth grade and so now we have all eight grades of primary education. If we want to go further and offer secondary education, we need to apply for affiliation with the Central Board of Secondary Education (SBSE). We need to meet many requirements for the infrastructure of the school including the classrooms´ size and equipment for a science lab, a library, we need to have prescribed teaching materials, and the necessary number of teachers with proper qualification.

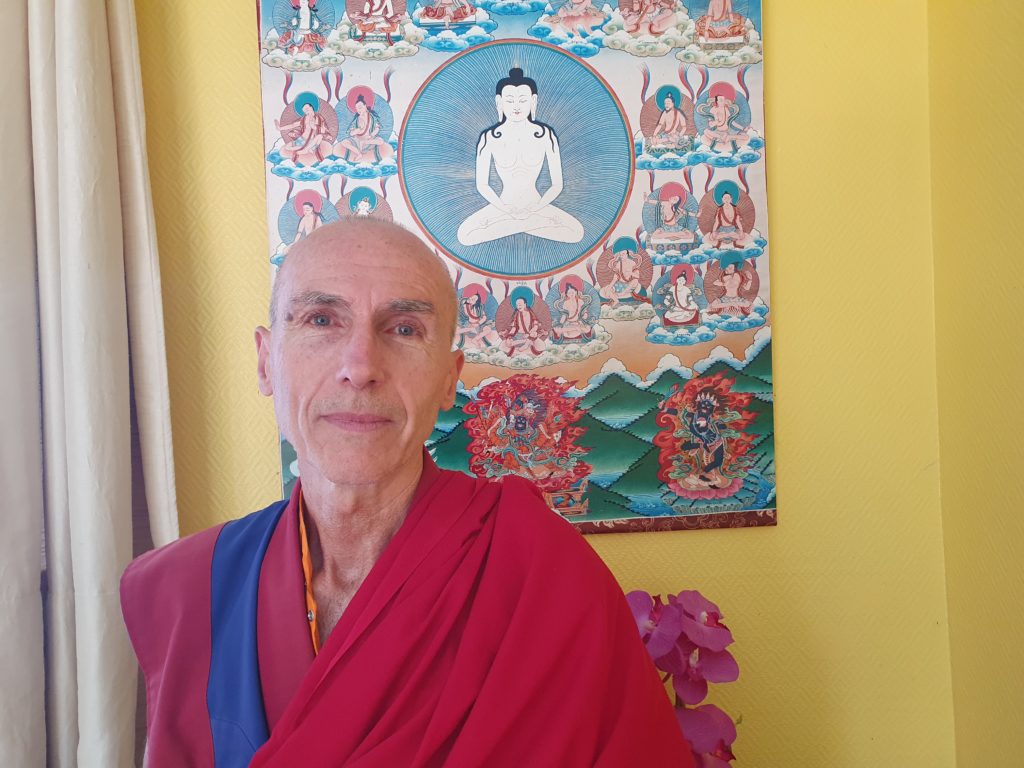

You are responsible for a monastery and also teach the western students which makes you travel a lot. Besides that, you have put an enormous effort in founding the school and you have a big burden of sustaining it on your shoulders. Why has it become one of your priorities?

Lots of people of my generation, including myself, did not have an opportunity of getting a good education when they were children. People could not study, not because they were not able to, they are smart, but an opportunity was not there for them. I finally obtained a good monastic education, but many others have been left with their potential unfulfilled. This is somehow sad to see. And this is still true for many children nowadays. In today’s world, without education they become very vulnerable. Many problems in our communities are rooted in the fact that people could not study and remain underprivileged.

Village primary schools in the remote mountains are generally poor and limited, so children cannot learn much. Life is difficult there and schools lack teachers, good teachers. Often lessons do not even take place, teachers do not come. When parents have a possibility, they send children to private boarding schools as soon as children can go there, in nearby or even more distant towns; there, education is better. But many families cannot do that, they do not have any financial means to pay the fees. Our school is there for the families who cannot pay and wish for their children education including traditional values and language. But we do not admit children on the basis of ethnicity. What matters is that families appreciate the curriculum and the opportunity that such a school gives to their children.

The school offers cultural and value education and teaching of the Tibetan language. Is it rare to get elsewhere?

Most schools in Nepal do not provide education in Tibetan which means that children of the mountainous regions, who are mostly ethnically Tibetan, lose the cultural background of their parents. Even if a family speaks a Tibetan (or Bhote) dialect, children are more fluent in Nepali and lack understanding of traditions which are all connected to the language. Our culture and values are less and less transmitted to the younger generation.

In the world which is changing dramatically in many aspects, it is a matter of urgency to save and preserve our language, culture and traditional values that have served humanity for thousands of years. They are still relevant.

Schools like the one we founded are very necessary to preserve the Himalayan cultural heritage. The formula is combining secular education with values and culture education, based on the knowledge of Tibetan language.

But the aim is not just to continue the ancient tradition. Such education will equip children well for their adult life. It will help them to find their identity and grow into knowledgeable and self-confident human beings. I can see it is happening, children at the school have blossomed wonderfully. It inspires me, it makes me see we have done the right thing.

Your monastery is in Kathmandu, but you built the school in West Bengal, in India. People may wonder why.

When we were deciding about the location of the school, Nepal was unstable politically and India seemed a more secure place. The city of Siliguri is well connected to Himalayan regions of India, Nepal and Bhutan, and is equipped with good infrastructure and modern facilities that are very important for education and health care.

It took fifteen years before the idea of building a school came to realization. Why so long?

Obviously, what has held us back mostly was lack of money. The school is financed with donations only.

We had to find a good location and purchase a piece of land for it, you do not do such a thing overnight.

Also, it took us quite some time before we got clearer ideas about how the school should be. Among other things, we created teaching materials in Tibetan language, reading books in Tibetan which contain stories related to the areas from where children come and explain various traditions of the people living there.

Then, when we had got some more money, we started building the school´s infrastructure. It is a boarding school, so we need facilities for both a hostel and classrooms. If we succeed in opening secondary education and have twenty five children per class, we would need a place for three hundred children.

There are many things to be done ahead of me, but I do not feel discouraged. It is worth all the effort.

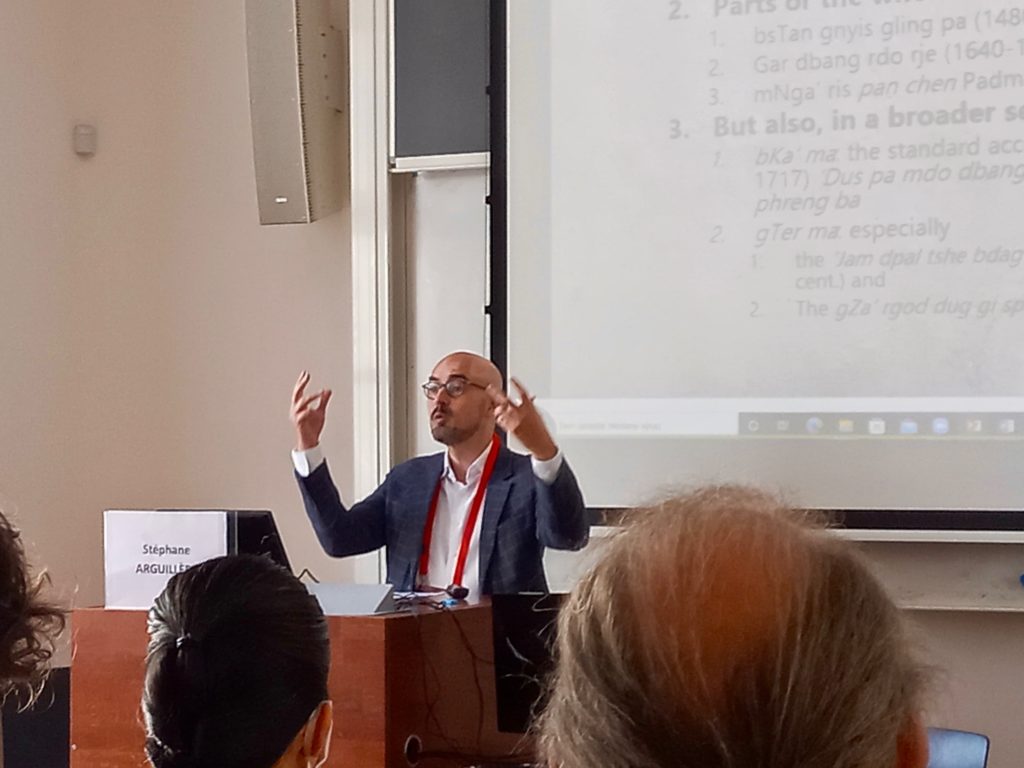

Khenchen Tenpa Yungdrung Rinpoche was born in Dhorpatan, a very remote area of western Nepal. At the age of 11, he entered the local monastery, Tashi Gegye Thaten Ling. After completing an initial course of study in Bön ritual texts and Tibetan calligraphy, he moved to Dolanji, India for further studies at the Dialectics School of Menri Monastery. In 1994, after successfully passing his exams and being awarded the Geshe degree, he went to Kathmandu, Nepal to continue his studies of Tantra and Dzogchen under the guidance of Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche at Triten Norbutse Monastery. In 1996, he was appointed as its Ponlop (Head Teacher) and in 2001 he became abbot.

Photos: Jitka Polanská, Celina Mejia

Read more about the school in this article: