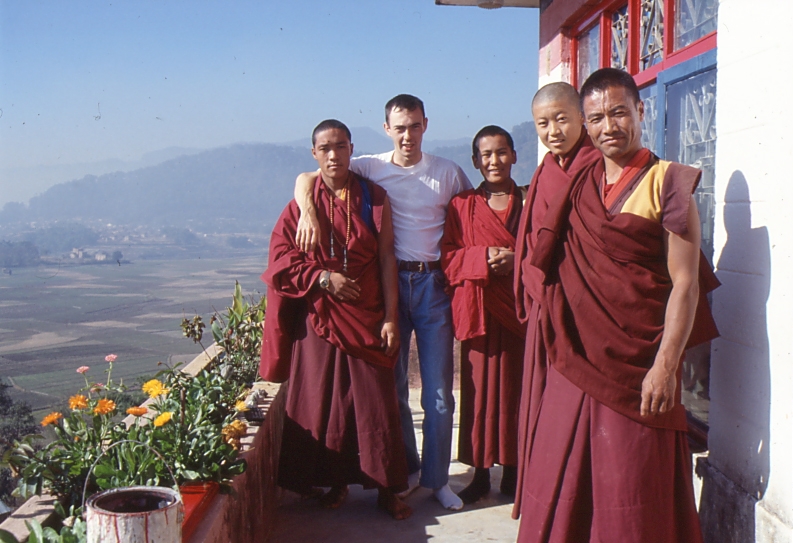

Martino Nicoletti initially approached the tradition of Yungdrung Bön as a researcher in anthropology. He visited Triten Norbutse monastery in 1990, when there were only rice fields around it and H.E.Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche was living and working there with other monks in very poor conditions. Later, Martino developed an interest in Yungdrung Bön as a practitioner. Now he lives back in his native Italy where he regularly has been inviting Khenpo Gelek Jinpa to teach, and he publishes Bön dharma texts translated from English into Italian in his small publishing house.

How did you first meet Bön, Martino? Was it through a book, a teacher or your research?

It was in 1990, in Kathmandu, thirty-four years ago. At that time, I was a student in anthropology at the University of Perugia, and I was working on my master degree´s thesis. It was exploring relationships between the Bön religion and shamanism. I went to visit Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche at Triten Norbutse monastery for that purpose. I requested an interview with him and he kindly agreed. We talked not one time, many times, actually.

You already knew about the existence of Bön?

I was very much interested in shamanism during my academic studies. Beside other things I was studying shamanism in some ethnic groups of Nepal and I found out that Bön also had aspects intersecting with shamanism.

Many people identify shamanism with Bön but Bön lamas point out that Yungdrung Bön is much more than that. In which area, according to you, does Bön contain spiritual procedures of shamanism?

When I spoke with Yongdzin Rinpoche about this, the shamanistic background of the Bön religion, he often spoke about it as a background of Tibetan culture, not something specific only to Bön, but rather to be common to all Tibetan communities. We could say that they all share this as a heritage.

In the Yungdrung Bön all the canonical works are classified into nice “vehicles” or “ways”. Four out of these nine are called “causal”, which means they depend on a cause. And those contain very similar beliefs, rituals and techniques as shamanism does: divination, therapy, ransom rituals… The remaining five are called vehicles or ways of “result ”or “fruit”. The ninth is the way of Dzogchen, the Great Perfection, which is the teachings received by many western students, which I became very interested in a few years later.

Let us get back to your visit to Kathmandu in 1990. What did the monastery look like at that time?

It was very small, with only a few monks there. Living conditions at the monastery were very poor. And it was not easy to distinguish Yongdzin Rinpoche from other monks.

He was doing the same things that they were doing, no difference. This astonished me because I knew I was meeting a very important lama. Every time I went to meet him, I met a very simple monk, helpful, overflowing with kindness and patience. It felt more like being in a family than in a monastery. And in relation with shamanism: there were some Tamang shamans coming when I was there. Yongdzin Rinpoche told me they visited sometimes, asking him for some advice.

The monastery at that time was outside the city, right?

Yes, there were just fields all around. Kathmandu was surrounded with ring road and after that you had to walk for about 45 minutes to to get to the monastery.

After some years, you developed interest in Dzogchen meditation, you said, becoming a practitioner. The dharma world and the academic world often keep distance but you found yourself in both of them.

It is true but I personally did not care much. I had reached a balance within myself of those two aspects and later I left the academic world altogether focusing on practice and independent research.

When did you start practicing?

It was while doing my first PhD in anthropology which had brought me to Kathmandu once again. I spent several years in Nepal, with some breaks, carrying out my research work about religion, rituals and myths of the Kulunge Rai tribe of Soluhumbu. Slowly, slowly, I started to become less interested in studying the Bonpo religion and more and more interested in practicing it, especially the Dzogchen meditation. In those periods, I had a chance to get some teachings privately from Yongdzin Rinpoche and they were a real booster for me to practice.

I remember you did some research about Chöd, didn’t you?

Yes, it was still within my academic work. I researched chöd practice in the Dolpo region of Nepal. I focused on the Chöd pilgrimage practiced in lower Dolpo, making a short documentary about it and I also wrote an essay and published it in English and Italian. We worked together with Riccardo Vrech on this research project. What I was mainly interested in was visual anthropology – using mainly visual means like photography and video for documenting research. We organized some exhibitions about the Chöd in Dolpo in Italy. Khenpo Gelek was present at the opening of one of them held in Rome. It was important for me already then but more and more over time not only research but also to disseminate knowledge about Bonpo culture to a wide audience. Later, I wrote some other works on Chöd and recently I have directed a documentary about Bardo accordion Bonpo tradition for French television. Khenpo Gelek features in this movie. Unfortunately, it is copyrighted so I cannot share it with sangha members even if I would like to.

You moved to France and lived there until recently, right? Now you are back in Italy?

Yes, after twelve years living in France I, together with my French partner, decided to live in Italy and moved there a few months ago. Now I live in Umbria, the region where I was born, close to Assisi, the birthplace of Saint Francis. Khenpo Gelek knows this region very well, he came several times and had very deep feelings connected to this area of Assisi and its surroundings. Sometimes, due to the nature of the landscapes we visited together and their specific energy, he told me he had the feeling of being In Tibet.

When did you invite him to Italy for the first time?

It was about fifteen years ago, I guess, and always in Umbria. And he was there this year too, in April, to give teachings.

Are Bön practitioners in Italy united, or rather scattered?

There are a few groups, not a unique sangha, but the number of people is growing. I personally feel a very close connection with Khenpo Gelek and that’s why I keep on inviting him to teach in Italy. Out of the same connection, I decided to build an independent publishing house, a few years ago, called “Le Loup des Steppes” (“The Steppe Wolf”). The name is inspired by the famous novel by Herman Hesse. The aim is to make important Bön texts and essays about Dzogchen available to the Italian public, to people who cannot read in English or French. I closely collaborate with John Reynolds and Jean-Luc Achard publishing their works, and also publish some audio recordings of teachings made during retreats, transcriptions of the teachings by Yongdzin Rinpoche and some traditional manuals of practice (i.e. Guru Yoga, Powa, Yeshe Walmo, Chod, Surchod, Bardo Monlam…). I want to share tools with people about how to practice. It happens often that lamas come, they teach and when they leave, there is no trace left. So, publishing text that help people continue with their practice and develop it is my way to contribute to creating a sangha.

How many books have you published?

More than twenty titles have been published till now. I started doing it in 2016 in France, this year I moved the activity to Italy.

Who translates the books, you?

Yes, mainly myself and another dedicated practitioner, Lidia Castellano. She helps when sending it to the publishing house to go on. We are basically the two of us.

How much of your time does it take?

I would say ten to twelve days a month. I do everything by myself, including the paging, graphic design of books, distribution. It takes lots of time.

What do you do to make a living?

I currently teach body awareness and dance-therapy. To develop my work and to fluidly combine my personal background as an anthropologist with the body-based therapy, in 2011, I got a second (practice-based) PhD in the UK in Multimedia Arts. Besides that, in 2004 I started to study Japanese Butoh dance. All these experiences allowed me to directly integrate dharmic activities with my profession and research. All these streams are in harmony with each other.

Photo credit: Martino Nicoletti