When families from remote villages of the Himalayan mountains send their children to a monastery, it does not necessarily mean that they want them to become monks. They do so also because the monastery will educate children in their native tongue and it will be free of charge. The founder of Triten Norbutse monastery in Kathmandu, H.E. Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche, has granted a refuge to many children but he has always felt it would be good for many of them to go to a proper school, a school which would give them a modern education but also transmit the meaningful traditional values of their communities. Here is a story of such a school.

Harsh climate conditions, poverty, lack of infrastructure, education and healthcare – all this makes the life of the people who live in the Himalayas difficult, even painful at times. Communities speaking Tibetan dialects have lived in the mountains for centuries, but now all families who have the means send their children to distant boarding schools to help them have a better future through education. Many of these boarding schools, though, do not teach the Tibetan language and culture and the children grow up disconnected from their mother tongue and from the traditions which have uplifted their people throughout the centuries. They may even become alienated from their own parents and relatives.

A large number of families cannot afford to pay any tuition fees and keep their children with them in the villages. But the mountain regions’ local schools have very poor teaching standards and do not refer to the native cultural and linguistic background of the Tibetan speaking population. Children from those families are probably going to experience the same cycle of hardships and life-long struggle as their parents.

Another educational option for families living in the high altitudes of the Himalayas is to send their children to a monastery. Monasteries accept children free of charge and educate them in their own language. However, a monastic curriculum is focused on traditional subjects and spiritual and cultural values and does not include a modern, secular education. Also, most children are not inclined to go to a monastery.

Triten Norbutse monastery in Kathmandu receives frequent requests from parents to take their children in. Its founder, H.E. Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche has granted refuge to many of those children but he always felt it would be better for them to go to school, a school which would give them a modern education but also transmit the meaningful traditional values of their communities.

Yongdzin Rinpoche´s disciple and the current abbot of Triten Norbutse Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung Rinpoche took it upon himself to build such a school, and it has become his long lasting mission.

The choice of a place

For this purpose, in 2007, Sherig Phuntsok Ling Bon Society, the founding organization of the school, was registered in West Bengal, a state in the northeast part of India. A parcel of land was acquired in the same year in Siliguri, the capital of West Bengal. The city was chosen for having relatively easy access to different corners of the Himalayas, being close to Sikkim, Darjeeling, Kalimpong, and only forty minutes drive from the border with Nepal. Bhutan is only one hundred fifty kilometers from there and it takes less than one day, traveling by car, to get to Kathmandu, where the monastic community of Triten Norbutse resides.

Another strong point is that Siliguri is ethnically, culturally, and linguistically very diverse. “It is a melting pot of the area and it has become an important cultural center. We thought it would offer good educational opportunities to our students, once they finished the school,” Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung says.

It took many years before sufficient funds were collected and the construction of the first building of the school started, in 2016. Architects from a France-based company Architecture et Dévelopment were involved in the planning. Together with local professionals, they designed an environmentally friendly and earthquake resistant structure. Natural materials like bamboo and local stones were used in some parts of the construction. The first building of the school included classrooms, a kitchen, a dining and meditation room, a library, separate dormitories for boys and girls, several staff rooms, a small dispensary, and toilets and bathrooms.

The opening of the new school was announced through the connections that the school team had in the mountains. “Also, two members of the team traveled to remote villages and spread the news there,” Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung says.

As a result, between January and March of 2018, around seventy children from different parts of the Himalayas of India and Nepal arrived and settled in the boarding school. Most of them belong to economically and socially vulnerable families whose values and cultural background are rooted in Buddhism and Bon, an ancient spiritual tradition very strongly present in the mountains in the past centuries. The school is free of charge for all the children.

Modern, yet traditional

Tise Himalayan International School (THIS), as the school is called, officially started with four classes in April 2018, when the new school year usually begins in West Bengal. “Everything went very smoothly. I was impressed by the good organization,” says Christine Trachte from Yungdrung Bon Stiftung, a German foundation which has supported the school since the very beginning.

Entrusted with leading the school was the President of Sherig Phuntsok Ling Bon Society, Ven. Sonam Norbu, who, in the previous fourteen years, had been responsible for the hostel and teaching Tibetan language and culture in the school in Lubra in Mustang. In the beginning, his core pedagogical team included a headmaster and four teachers. Two of them teach Tibetan language and culture.

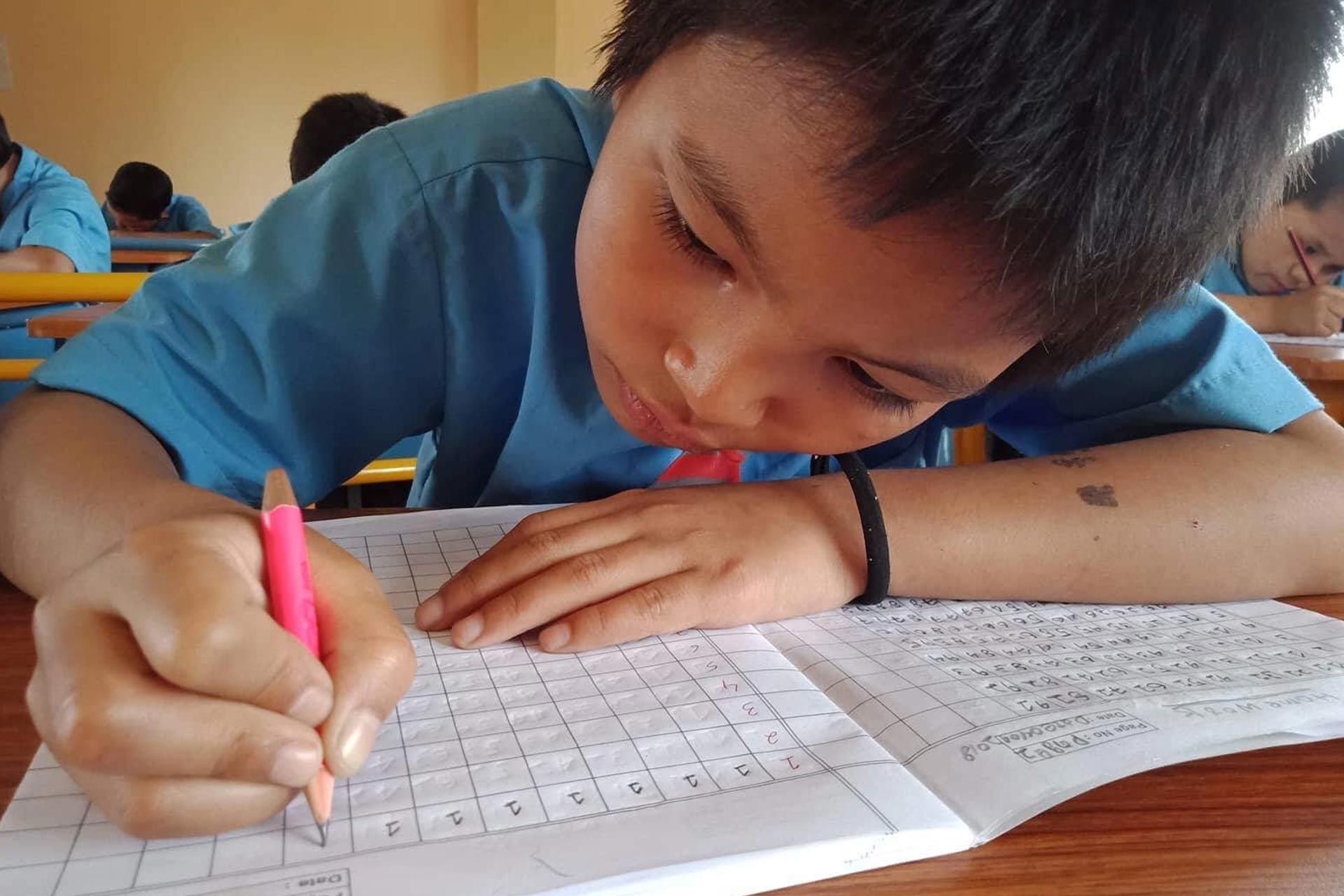

The school’s curriculum is quite unique. It meets the educational standards required by the government of West Bengal and the Central Board of Secondary Education, but it is enriched with elements of the art, culture, and history of the Himalayan regions and emphasizes the environmental awareness and respect for nature typical of the traditional spirituality.

“We worked very closely with Khenpo Tenpa Rinpoche and Sherig Phuntsok Ling Bon Society to define the added value of the school, thinking of how to unite a rigorous scientific approach to the education and the rich traditional background of the Himalayan culture. We had so many meetings about it,” Mara Arizaga says. She is one of the founders of EVA (Enlightened Vision Association), a non-for- profit organization based in Switzerland that focuses mainly on the preservation of the cultural heritage of the Himalayas and for many years, has been helping the school in various ways.

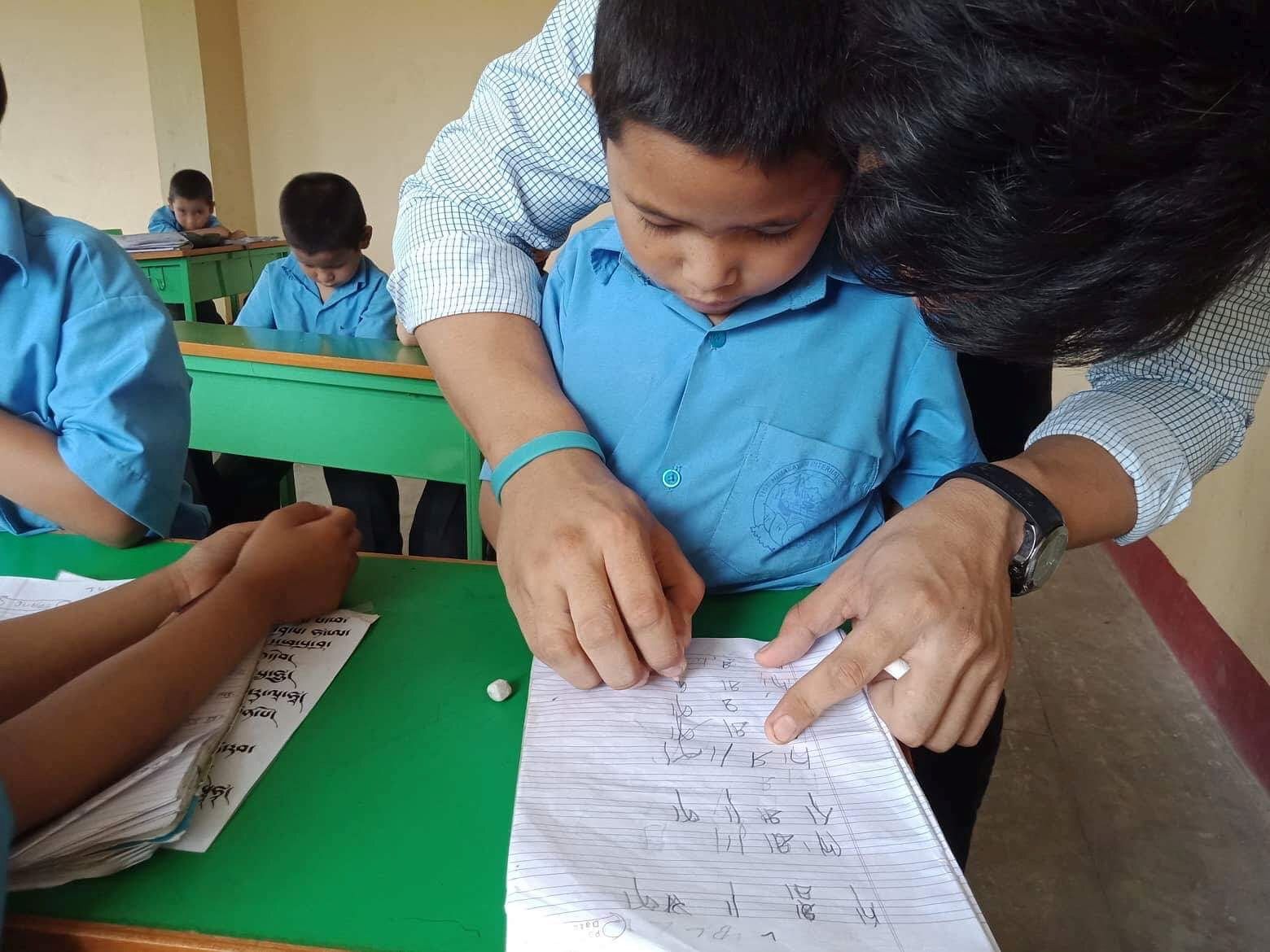

The school has a holistic approach to education, engaging students´ body, speech and mind in the learning. It gives opportunities for children to practice sports and dance, as well as traditional Himalayan yoga. Students are introduced to meditation and naturally exposed to the traditional spiritual values of empathy, generosity, and open heartedness.

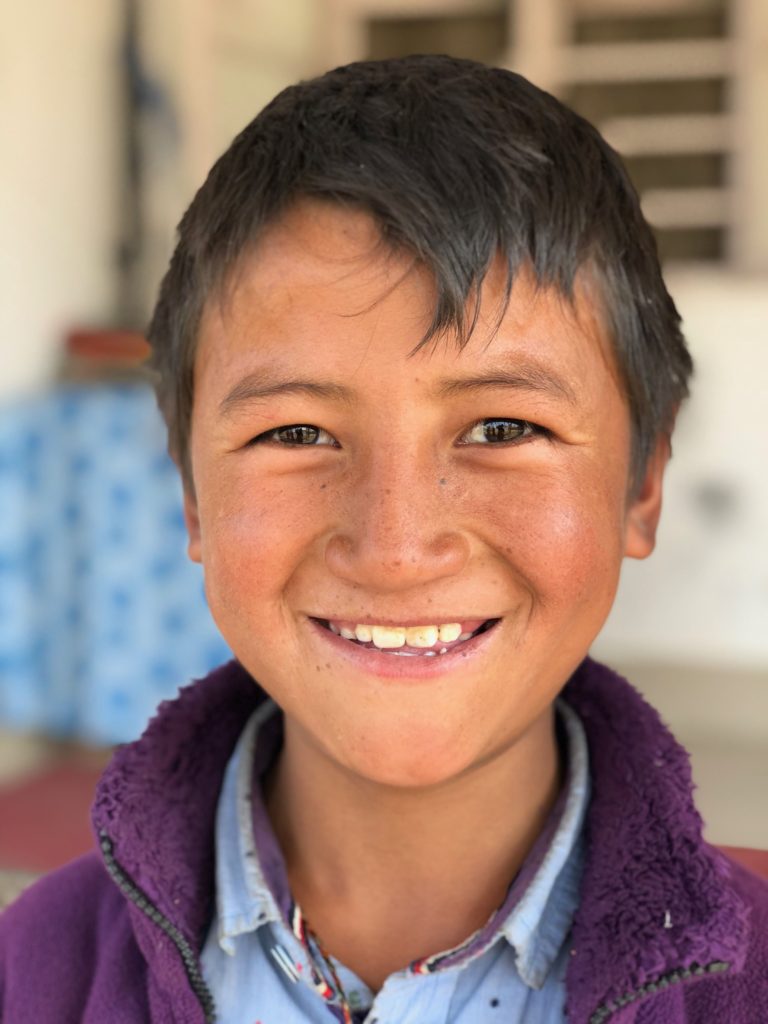

A visitor to the school can see lively and self-confident children. Although they are far away from their parents for long periods and often cannot visit them even during the holidays, they know that this is a great opportunity for them to display all their potential. This helps them overcome homesickness.

To keep their connections with their homeland alive, THIS produced its own textbooks for learning Tibetan with stories which introduce children to personalities, mountains, or rivers of the areas they come from. Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung formed a team of people who researched and collected those stories and created texts based on them.

Sometimes, parents come to visit the school. Aged prematurely by hard labor, they are visibly moved to see their children blossoming into a life they could never have dreamt of for themselves.

The hard way

Currently, THIS has seven classes and provides education for 138 children, half of them girls. Promoting equal opportunities for girls is one of the objectives of the school. Eleven teachers, a nanny, and a cook take care of the children. In addition, four members of Sherig Phuntsok Ling Bon Society work for the overall welfare of the children, managing also the school´s administration and carrying out projects related to the extension and development of school buildings.

The school neither receives governmental financial support, nor collects any tuition fees which means it is completely dependent on donors. Its financial sustainability is a big challenge, but Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung is uncompromising in his objective to keep the high standard of the school. “Charity schools like ours sometimes cannot offer the best education because they lack funds, but we want to be an outstanding school no matter what,” he says. “Lowering standards would be humiliating for children and their dignity is very important to me. I want the school to give them certainty that they are as good as anyone else and perfect as they are,” Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung says.

He himself is a donor, giving all he receives as a dharma teacher to the school and he has been tirelessly working to increase donations, sending out applications for funding, following up every opportunity that arises. People from Sherig Phuntsok Ling Bon Society, the German Foundation Yungdrung Bon Stiftung, and the Swiss organization EVA support him in his efforts, as do other organizations and individuals. Still, funding is not sufficient for the moment. “We are always balancing on the edge,” Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung says.

One of the priorities he mentions is to increase the teachers’ salaries and give them more stable work contracts so that they feel less uncertainty. The salaries that the school can afford to pay at the moment are still far from being attractive.

There is also an urgent need to finalize the construction of the second building, a three-story structure started in 2020. It contains fifteen classrooms, teachers’ offices and working space, and toilets. More than a half of the cost has already been paid and the construction company continues to work with the promise of being paid when more finances become available.

The school also needs a new dormitory for girls so that more children can be enrolled, up to the full capacity of 300 students, 150 boys and 150 girls, with an average of 25 children per class, and 12 grades altogether. The school aims to cover a complete secondary education.

In the future, Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung´s wish is to build a small clinic on the school’ s property. The healthcare facility would have a double function – taking care of the health of the school’s community and also preserving and developing the traditional medical science of the Himalayas.

“The Himalayan medical knowledge and the tradition of respect for nature may have a word to say in the present world which is facing imbalances and extensive environmental degradation,” says Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung.

He believes that the school will not only benefit the children but also have a positive influence on the world around them. “Wherever they go afterwards, whatever life career they pursue, the values they have been taught will stay with them,” he says.

Photos: archives of Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung Rinpoche, Jitka Polanská, Darek Sawczuk

(After having read this article, some readers asked us about how to help. If you have the same question, look HERE.)