Stéphane Arguillère met Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche in 1992, as a twenty-two year old young man. Later, he became involved in the sangha as it gathered around Shenten and started the Shenten´s newsletter Speech of Delight which has transformed into the current magazine. He has translated Yongdzin Rinpoche´s and other lamas´ teachings in past years and now pursues a career as an academic. As Stéphane says in his account, his life has encompassed many challenges but the direction is from dark places to the light, and not vice versa.

First of all, let us speak about the Speech of Delight, Stéphane. You and some others started it, right? I have some old issues with me, we can take a look at them together, on the screen. The first one is from 2006, the last one from 2010.

That first one I made myself. I can see some typos (he laughs). I do not remember who brought up the idea, but I remember that Yongdzin Rinpoche was very enthusiastic about it. I think we copied a bit of the customs from the Dzogchen community, as there were some people in our sangha who were students of Namhkai Norbu. They had a newsletter in France, how was it called? Le Chant du coucou – The Song of the Cuckoo. I think the idea may have been from them. It was a time when there were no websites, I mean dharma centers did not have websites, so some vehicle was needed to distribute information. The frequency, I think, was twice a year.

You also told me that Yongdzin Rinpoche gave it the name.

Yes, it was him and he also made a drawing which was meant to be the logo of the bulletin. His style is quite recognizable in it. It is a vase, you see, a symbol of wealth, like an empowerment vase but without a spout and there was a jewel at the top.

You can also notice a small poem of Rinpoche written in the second issue of the newsletter.

I see, and I see also a shift in the image, a development. Somebody took over the graphical design?

Yes, Christophe got involved. It made the newsletter much nicer, but complicated its edition quite a lot, as new typos and spelling mistakes would pop up as he was managing the text in the layout. He absolutely wanted it to be beautiful, no matter what (he laughs).

This is a usual conflict between the graphic designers and content creators, I would say. Who was in the core team of the newsletter, at the beginning?

I think I was responsible for it, but I didn’t do it alone. It was written in English, and I am not a native English speaker. If I remember well, Carol Ermakova helped with it. And we published content that other people prepared. We were asking all the people who were responsible for something to write down a report, a small summary of activities. It was organized like in the Dzogchen community: a group of people was formed and each of them was assigned with different responsibilities. Not much hierarchy. The purpose of the newsletter was to show the people in the community what was happening at Shenten to raise funds and to make them feel Shenten is a common thing. As you see, there is also a call for help in karma yoga.

Now there is a more cautious approach to call people to stay as volunteers. Help can come with troubles sometimes…

This contradiction was there from the very beginning. And it is something that I saw in many Dharma centers. But there was a great need for help and money just to keep things running. When I was in the administration of Shenten, on the management board, I saw how much money was needed just for regular maintenance, merely to ensure that the structure does not collapse. My idea at that time was to get regular donations from people rather than financing the center through the teaching fees. I thought that if we made people pay just for teaching sessions, it would not make them feel responsible, they would feel more like consumers. And I also imagined that generosity would come with transparency of our intentions and results.

The first issue was very sober and succinct but then the newsletter started to contain longer articles and stories with pictures, also quite detailed reports of Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung Rinpoche.

As for Khenpo´s letters, yes, we asked him to write one, as we did not want to bother Rinpoche with that, and he was very much willing to do it. Maybe he was less busy than he is now. At the beginning, I made the newsletter very cheap, intentionally, because it was meant to be distributed in paper; but gradually we started to send it through emails and costs decreased, and we could afford to use colors and pictures.

As you can see, in the second issue there is a report about a project of translating chosen Bon texts – which was a project which I initiated. We wanted to raise funds which would enable translators to work on it. But, unfortunately, it did not work.

Do you remember until when you were involved in the newsletter?

Not really. At some point I passed it to someone else, I do not recall when and to whom. You know, the years 2008-2010 were very difficult for me, in many aspects. I faced lots of obstacles and maybe that’s why I forgot lots of things from that period. My relationship with the Tibetan things, my professional life, everything went a bit upside down, and also the connection with Shenten loosened. At the beginning, things were very fresh, a bit anarchic and funny in Shenten, and we all were very enchanted with it, and a bit naïve about it. One of the first times when we were sitting with Rinpoche on the bench in the courtyard outside, I told him: “Oh, Rinpoche, I have been through so many Buddhist centers and it was always hell on earth, while here, it is so nice and people are so relaxed and there is such a practice atmosphere!” And Rinpoche laughed at me, saying: “Just wait a little bit and you will see” (he laughs). And he was right, of course. With time, it wore me out somehow and finally, I used to come only to translate. I think that the last time I came, as an interpreter, it was for His Holiness the 33rd Menri Trizin, when he visited Shenten in 2010. Khenpo Rinpoche asked me, he needed someone who could translate directly from Tibetan into both French and English.

You were already so good in Tibetan?

I started learning Tibetan when I was eighteen, in 1988, and I was forty at that time. I was already good enough in Tibetan when I met Yongdzin Rinpoche in 1992 to discuss in Tibetan with him. Actually, my spoken Tibetan was better when I was thirty than now, because I do not use it very much. My classical Tibetan is good, I can read texts fluently and my understanding of Tibetan lamas when they are teaching is ok, but I do not get much practice these days in talking. Speaking about modern life is especially difficult. I would not be able to say something like: “Go to the website and download that file”, I have no clue about some of these modern words.

Maybe they say “website” and “download”, I would not be surprised.

Yes, my colleague at the Institute of Eastern Languages (Inalco) in Paris keeps correcting Tibetans. She has an amazing vocabulary in modern spoken Tibetan, and she teaches them all the neologisms that are used in Lhasa.

When lamas speak Tibetan, do you understand some of them more easily than others?

Definitely, Khenpo Rinpoche is very easy to understand, he speaks the common language of the Tibetans in exile, with much less regional accent than, let us say, Khenpo Gelek or Geshe Samten – geshe la has a really strong accent from Rinpoche´s native region, Khyungpo. I also translated for the latter lamas, but I had to make an effort. Translating Khenchen Rinpoche is very easy, instead.

You said you met Yongdzin Rinpoche in 1992. Was it at Triten Norbutse?

Yes. And then, I returned to Triten only in 1998. And it had already grown a lot.

How was the monastery in 1992?

It is a bit difficult to describe, because the few old buildings are still there, but they are sort of completely taken into the extended structure. It was already a busy place and very much in the process of building. But below the monastery there were only rice fields, no city, only a few houses around the Swayambhu hill. The flat part between the Swayambhu stupa and Triten, which is now filled with houses, was just open countryside. I remember that when I was visiting, the taxi dropped me at the Swayambhu hill and I had to walk through all those rice fields for more than half an hour. There were little walls made of ground between the fields and I remember myself walking on them to the monastery.

You were a student of Tibetan language and culture at the university at that time?

Yes, in 1992 I basically completed my studies in both Western philosophy and Tibetan language and civilization. I learned Tibetan very quickly because my first master, Nyoshül Khenpo (a Nyingma lama) told me, when I was seventeen: “You cannot speak Tibetan, I do not speak English, if you do not learn Tibetan, I will not teach you.” So I learned as you can do when you are only eighteen, it becomes your only obsession. After five years, I got the French highest teaching degree (“agrégation”) in philosophy, which granted me to get a civil servant position as a highschool teacher automatically. But in those days I was not interested in any such thing. I wanted to become a monk and practice under the guidance of my masters. So, in 1992, I went to Nepal, waiting to get an invitation for Bhutan where my teacher, Nyoshül Khenpo, lived, but it did not work as I expected, and actually, that trip was a failure – or rather, things occurred in a completely different way than what I had imagined. For example, this was the first time in my life that I came in contact with Bon masters and monks, which was then just a mere curiosity for me.

You mentioned obstacles and crises several times, but my impression is that you are a very happy person now. Is this correct?

Yes, it has gotten better and better. I was one of those young men who thought that if they do not achieve things by the time they are thirty, they will never achieve anything at all. I went through very bitter things, and at some point I must admit I lost hope. I got a very clear prophecy from another of my Nyingma masters, Chimed Rigdzin Rinpoche, that I would become “a big professor”, as he said in his weird English – he even specified it very precisely, and it would be a quite strong position on Tibetan religions in France. But my own desire was only to receive the instructions and then to put them into practice, and I had no serious appetite for an academic career at that time; and later on, I resigned myself to this prophecy, as it has been so long in coming, I thought it would never come true. I was never properly supported in French tibetology and even ended up facing many serious obstacles, hostilities, in my thirties and early forties. At some point, I told Yongdzin Rinpoche that I was so fed up with all that, as it was so depressing, that I wanted to drop it all and focus on practice. But he told me: “No no, don´t. If you don’t get the title you deserve,” he said, “however interesting the things you are saying or writing may be, people will not take them seriously.”

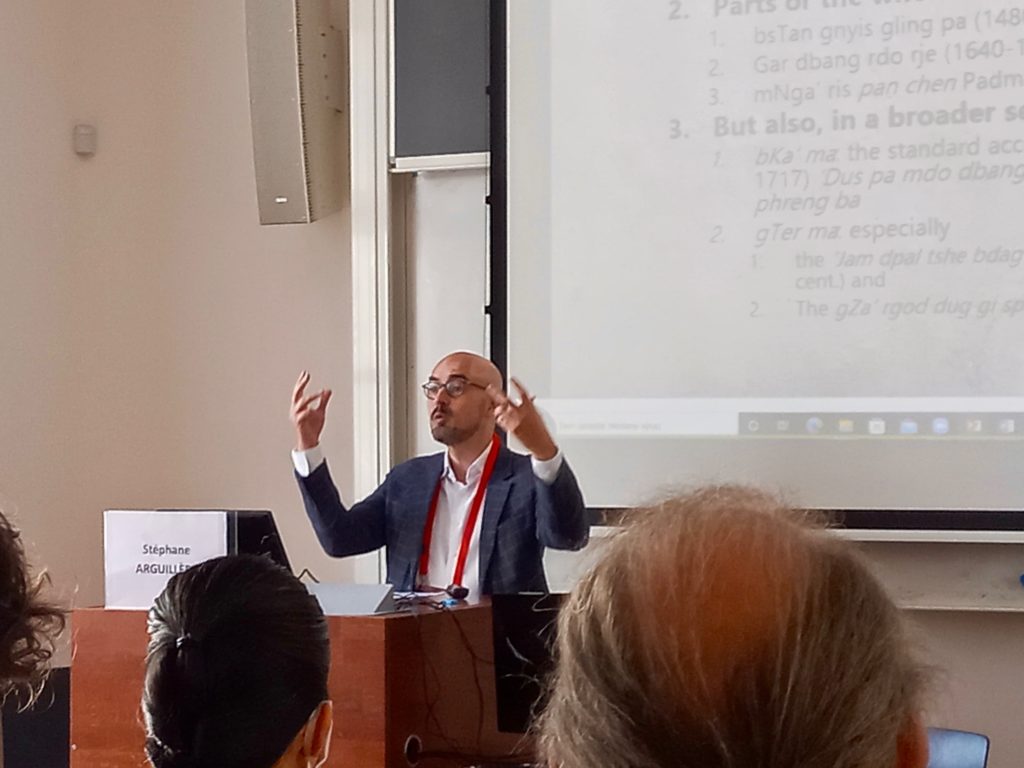

Then, I somehow persevered, as I could. Now, at last, my career has become more successful, as I am an associate professor in Tibetan language and civilization, expecting to be promoted to a full professor soon, plus, for example, I run a collective research project on the history of the “Northern Treasures” branch of the Nyingma school, financed by a generous grant from the French National Research Agency. I am also responsible for the training of the French high school philosophy teachers so as to enable them to teach non-Western philosophers, including the Buddhist author Nāgārjuna. Now, I can let go of all the bitter things of the past. I enjoy the present because it is so unusual for me that everything goes so smoothly (he laughs). The only thing I could complain about is that I am working little bit too much – but, basically, it is my fault.

Do you still feel a part of Shenten´s community, or any other community, for that sake?

These days, I am making stronger and stronger connections with the branch of Nyingma school called the “Northern treasures”, which is also my research topic. But I still feel at home in Shenten, even if I am not coming that often anymore. I have a very good relationship with Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung Rinpoche – I would say it is a friendship. We get along very well, anyway. I think he was a bit disappointed that I left suddenly, at some point. I surely did too much for a long time, and then suddenly dropped everything because I was mentally exhausted. Khenpo la does not surely blame me, but I think it saddened him, with the idea that I was abandoning Yongdzin Rinpoche. But, when it happened, my overall situation was really too heavy for me. Yongdzin Rinpoche somehow perceived it himself. Just before everything collapsed on my head, I met him in Paris to interpret for one of his teachings, and then he gave me, very discreetly, as a monk, a bottle of Polish vodka with golden leaves in it, saying with a smile: “Maybe you will need it”. I actually made lots of offerings to the Protectors with that alcohol, and even drank a part of it, but, though it was a bit of a consolation, it was not enough to cope with all the obstacles at that time. A very sweet attention anyway.

Maybe, after all, those moments when everything falls apart and you lose hope and orientation are also part of the path, especially for us Westerners, who come to the Tibetan teachings with quite a lot of unrealistic expectations. Maybe it starts becoming serious only when you have got rid of all these expectations and still get back to it, with a fresher mind, “devoid of both hope and fear,” as it is said in the Chö teachings as well as in Dzogchen.

Photo credit: Stéphane Arguillère